Everything you need to know about Uranus

by Scott Dutfield · 25/02/2020

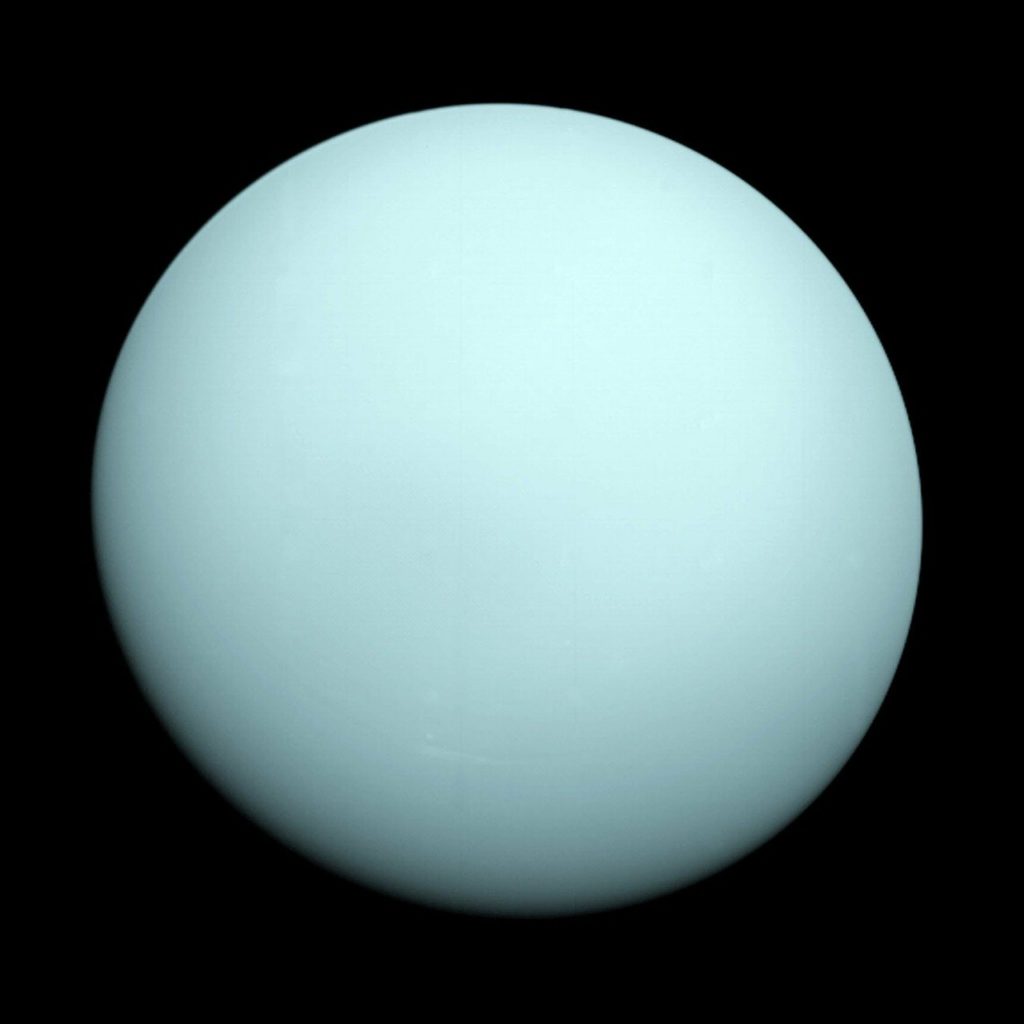

Seventh planet from the Sun, third-largest and fourth most massive in the solar system. Uranus was the first planet to be discovered by telescope

Four times the size of Earth and capable of containing 63 Earths inside it (it is only 14.5 times as dense, however, as it is a gas giant), Uranus is the third largest and forth most massive planet in our solar system. Appearing calm and pale blue when imaged, Uranus has a complex ring system and a total of 27 moons orbiting its gaseous, cloudy main body. Due to its distance from the Sun the temperature at the cloud-top layer of the planet drops to -214°C and because of its massive distance from Earth it appears incredibly dim when viewed, a factor that led to it not being recognised as a planet until 1781 by astronomer William Herschel.

Atmosphere

Uranus’s blue colour is caused by the absorption of the incoming sunlight’s red wavelengths by methane-ice clouds. The action of the ultraviolet sunlight on the methane produces haze particles, and these hide the lower atmosphere, giving the planet its calm appearance. However, beneath this calm façade the planet is constantly changing with huge ammonia and water clouds carried around the planet by its high winds (up to 560mph) and the planet’s rotation. Uranus radiates what little heat it absorbs from the Sun and has an unusually cold core.

Rings

Uranus’s 11 rings are tilted on their side when viewed from Earth and they extend out from 12,500 to 25,600km from the planet. They are widely separated and incredibly narrow too, meaning that the system has more gap than ring. All but the inner and outer rings are between 1km and 13km wide, and all are less than 15km in height. The rings consist of a mixture of dust particles, rocks and charcoal-dark pieces of carbon-rich material. The Kuiper Airborne Observatory discovered the first five of Uranus’s rings in 1977.

Structure

Uranus consists of three distinct sections, an atmosphere of hydrogen, helium and other gases, an inner layer of water, methane and ammonia ices, and a small core consisting of rock and ice. Electric currents within its icy layer are postulated by astronomers to generate Uranus’s magnetic field, which is offset by 58.6° from the planet’s spin axis. Its large layers of gaseous hydrogen and constantly shifting methane and ammonia ices account for the planet’s low mass compared to its volume.

Orbit

Uranus takes 84 Earth years to complete a single orbit around the Sun, through which it is permanently tilted on its side by 98° – a factor probably caused by a planetary-sized collision while it was still young. Due to its sideways positioning each of the planet’s poles points to the Sun for 21 years at a time, meaning that while one pole will receive continuous sunlight, the other will receive continuous darkness. The strength of the sunlight that Uranus receives on its orbit is 0.25 per cent of that which is received on Earth. There is a difference of 186 million kilometres between Uranus’s aphelion (furthest point on an orbit from the Sun) and perihelion (closest point on an orbit from the Sun).

This article was originally published in How It Works issue 08

For more science and technology articles, pick up the latest copy of How It Works from all good retailers or from our website now. If you have a tablet or smartphone, you can also download the digital version onto your iOS or Android device. To make sure you never miss an issue of How It Works magazine, subscribe today!å