How did the Himalayas form?

by Ailsa Harvey · 16/10/2020

One collision created a diverse land of culture, ecology and the world’s tallest point

(Image credit: Bijay Yadav/ Pixabay)

Covering close to 600,000 square kilometres, the Himalayas are a mountaineer’s playground. With over 50 mountains exceeding 7,000 metres and home to ten of the world’s 14 highest peaks, the choice and range of required skill sets provides a challenge for explorers of all abilities.

Some of the earliest people to venture into the Himalayas were traders and pilgrims. Like most who have visited the area, pilgrims took to the mountains in search of a test. Through religion, they saw the Himalayas as an environment of physical extremes. They believed that the more testing their pilgrimage was, the more worthy they became of salvation. And what place is more testing than the Himalayas?

Divided into three geological zones – the Outer Himalayas, the Middle Himalayas and the Great Himalayas – the environment ranges from the tropics down below to the jagged peaks that cut into the clouds. Passing through five countries –India, Pakistan, China, Bhutan and Nepal – it is no wonder the Himalayas are so varied. The further down you explore into valleys shadowed by steep slopes, the more variety in life you’ll find – from the mountain-dwelling creatures who have adapted to suit this unique environment to the settlements and villages below the snow line who live off the resources from the mountains.

Initially it was believed that the earliest human inhabitants lived in the area no earlier than 5,200 years ago. Now, however, evidence in the form of ancient footprints solidified into mud dates the start of mountain life between 7,400 and 12,600 years ago. While the high-altitude areas of the Himalayas are not the easiest places to live, at this time the region would have been more humid, and agriculture could have been better supported higher up in the mountains.

The climate continues to change to this day, shaping a new version of the Himalayas. With growing concern over the implications of global warming, nations surrounding the mountain range are working together to protect the land they not only admire, but depend on. More than 240 million people have made the peaks and crags their home, and amid the climate crisis are seeing some of the most dramatic impacts take a toll on it.

Making the mountains

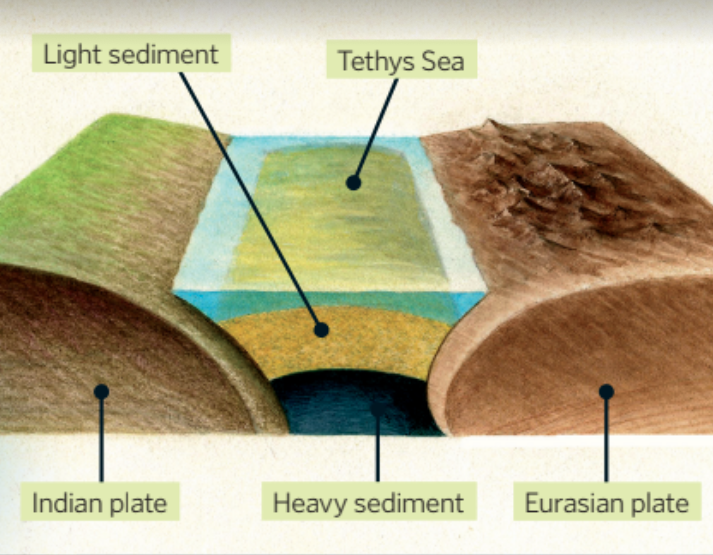

As an isolated island, 200 million years ago India started drifting in the direction of Asia. Millions of years later, its collision with the mainland would create the world’s highest mountain range.

60 million years ago

As India inched further north, the width of the Tethys Sea gradually decreased. When India reached Eurasia, a landmass of similar rock density, the sediment making up the Earth’s crust felt an extreme force from both directions. Initially, because the two continental plates were of equal buoyancy, neither could push the other down underneath itself in a process called subduction. As the sea became narrower and pressure rose, the only option in relieving it was to throw the crust between them upwards.

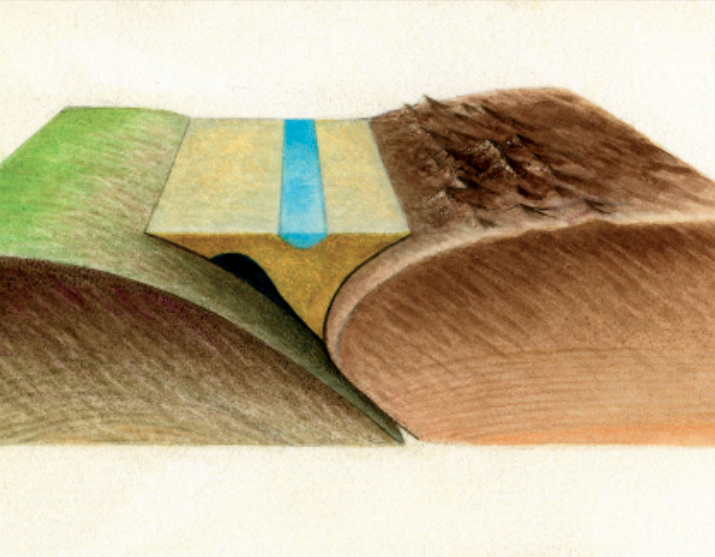

40 million years ago

The heavier sediment at the floor of the Tethys Sea was able to force its way underneath the Eurasian plate over time. Meanwhile, India continued to push the base of the Eurasian plate, settling in position underneath it. The Indian plate kept moving, but slowed to half its original speed following the collision.

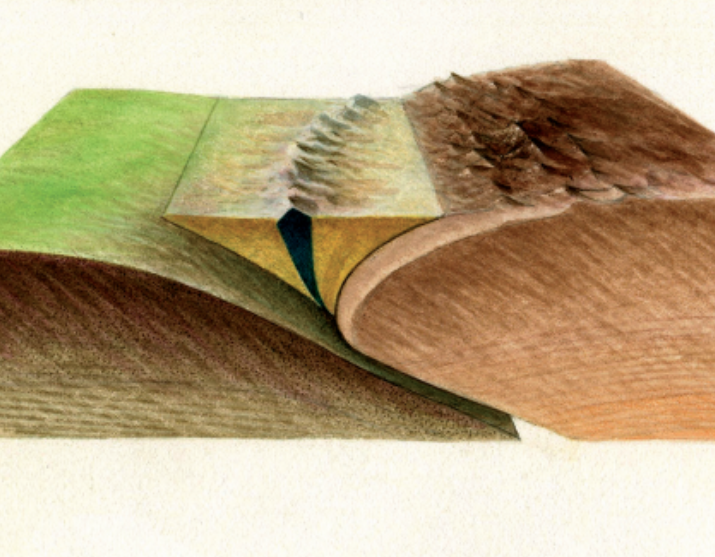

20 million years ago

After the Tethys’ sea floor was forced downwards under the plates, only some heavy sediment remained. This sediment, wedged between the colliding plates, started to crumple upwards. This creased land was the early creation of the Himalayas, in place of the sea’s disappearing water. Tibet, part of the Eurasian plate, began to rise with it.

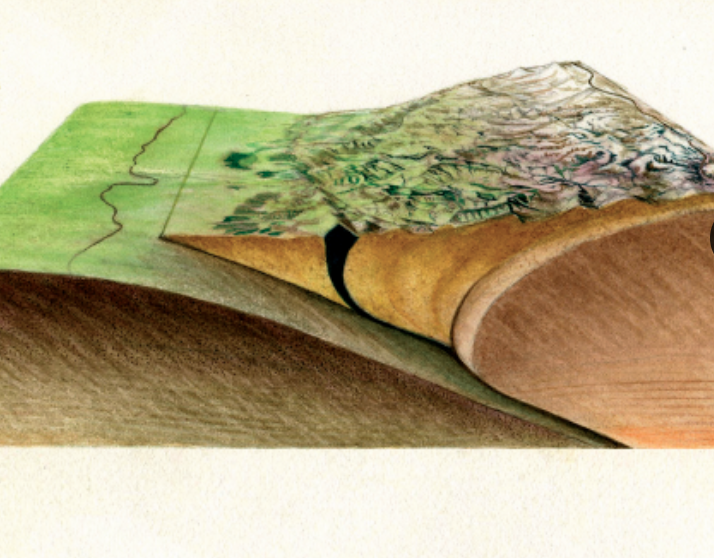

Today

19-kilometres deep underneath the surface of the Himalayas, the Indian plate is still pushing northwards under the Eurasian plate. As the two plates continue to press against each other, the forces are pushing the Himalayan mountains marginally higher as every year passes.

10 million years from now

If the plates continue to move over each other at the current rate, Nepal’s opposite borders will overlap each other, and the area where the country once was will no longer line up. As Nepal ceases to exist, the Himalayas – at the tallest they will have ever been – will be located near the Indian border.

(Illustrations by The Art Agency/ Sandra Doyle)

The king of the Himalayas

As the world’s highest mountain, Mount Everest is at the top of many extreme explorers’ lists. Others leave the peak of danger and uncertainty to the most daring and elite. As an attraction bringing hoards of tourists to the Himalayas, only a few make it to the summit. Every year since 1990, at least one person has died in pursuit of reaching its highest point.

The first official attempt to climb Mount Everest was in 1921 by a British team, but it wasn’t until 29 May 1953 that the first mountaineers made it to the top – 8,848 metres above sea level. Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary climbed all the way up with the knowledge of the mountain’s history of taking life. Of the few who had tried before them, many had not returned, but their adrenaline and desire to succeed overcame their fears. Since then about 5,000 people have climbed Mount Everest, and more than 300 people have died trying.

While a stunning spectacle looming over Tibet and Nepal, history tells of the extreme conditions on Everest. A combination of the human body’s inability to cope with such altitudes, freezing conditions and the length of time exoposed to the elements over the distance travelled means there’s an area of the Himalayas only the elite can successfully experience. Even then, the unpredictability of rock and ice falls, avalanches and earthquakes make for the powerful and unforgiving personality that is Mount Everest.

For more science and technology articles, pick up the latest copy of How It Works from all good retailers or from our website now. If you have a tablet or smartphone, you can also download the digital version onto your iOS or Android device. To make sure you never miss an issue of How It Works magazine, subscribe today!