How do we sense time?

by Scott Dutfield · 03/04/2019

The science behind why time flies when we’re having fun

When you are waiting for a bus you can usually estimate how long you’ve been standing there. Our ability to keep track of time is important in almost every aspect of day-to-day life, from playing a musical instrument to holding a conversation.

That little internal alarm that says you’ve been standing in the shower for too long comes from a type of temporal processing supported by two neural clocks. Researchers previously thought that our intuitive timekeeping ability came from a part of the brain called the striatum. Studies have shown that this region is activated when people pay attention to time, and patients with Parkinson’s disease – which disrupts the striatum – can have difficulty telling the time.

Scientists predict that the striatum consistently pulses with activity, a little bit like the ticking of a clock. However, recent studies suggest that in order to be conscious of the passage of time your brain also relies on the hippocampus to remember how many pulses from the striatum have occurred. This concept is known as the interval timer theory, and it explains how we unconsciously judge time spans on the scale of seconds to hours.

You will notice that time spent with your friends seems to pass much faster than when you’re writing an assignment. Neuroscientists have found that this is because your brain stops recording these pulses of activity when you stop paying attention to time, such as when you’re engrossed in an activity. When this happens, the brain puts fewer ‘ticks’ of its internal clock in storage, making it feel like less time has passed.

On the other hand, in situations where you are more actively aware of the time – like when you’re waiting for a delayed appointment – your mind will be counting every tick because you have little else to distract yourself with, making the passage of time feel much slower. So the next time you find that the day is dragging on, try to take your mind off the time to distract your internal clock.

Your brain’s internal clock

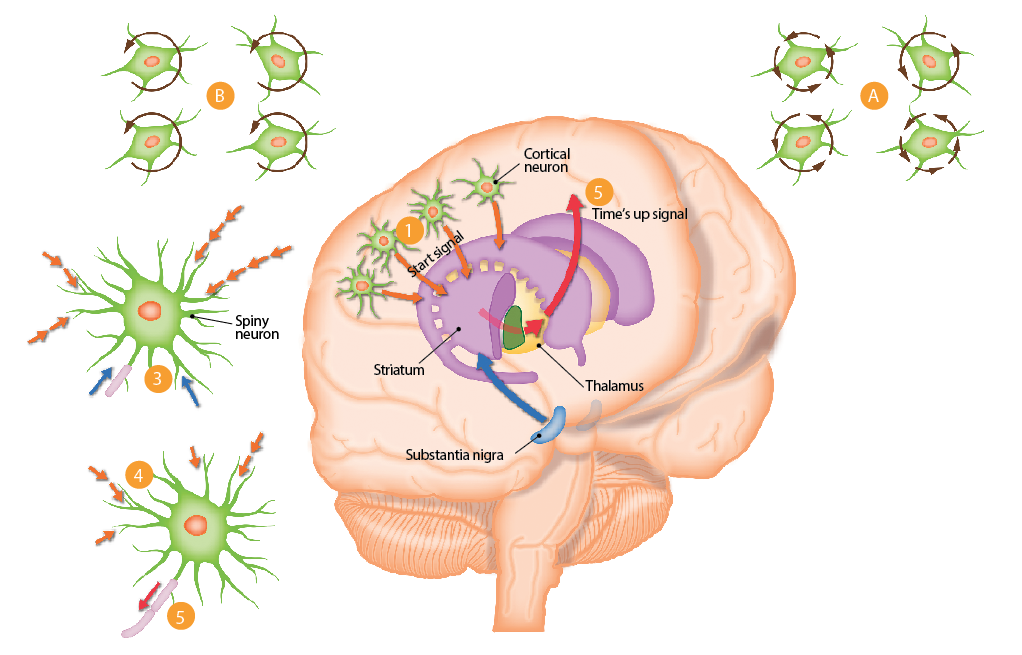

The interval timer theory explains how your brain keeps time like a neurological metronome

A ‘start’ signal is activated by the onset of an event that lasts a familiar amount of time, such as the three minutes it takes to boil some water in a kettle.

This triggers specific cortical nerve cells (which usually fire at different speeds, shown in A) to briefly fire together at the same time (B). They then return to their original firing rates, but because they all started simultaneously their activity follows a particular pattern.

A subtype of brain cells called spiny neurons monitor the cortical neurons’ activity, keeping track of how many times their firing patterns repeat. When the event finishes – in this case, once the kettle has boiled – bursts of dopamine are sent towards the striatum.

The release of dopamine causes the spiny neurons to commit the firing pattern of the cortical neurons at that particular instant to memory. This creates a kind of ‘time stamp’ for the given event. Research suggests that there are unique memories for a whole range of different intervals.

Now the spiny neurons have ‘learned’ these intervals they will monitor cortical firing rates until they match the memory for the time stamp that signals that particular event is over. Once this occurs the striatum sends signals to other areas of the brain involved in memory and decision making, giving you an internal ‘time’s up!’ alert.

This article was originally published in How It Works issue 110, written by Charlie Evans

For more science and technology articles, pick up the latest copy of How It Works from all good retailers or from our website now. If you have a tablet or smartphone, you can also download the digital version onto your iOS or Android device. To make sure you never miss an issue of How It Works magazine, subscribe today!