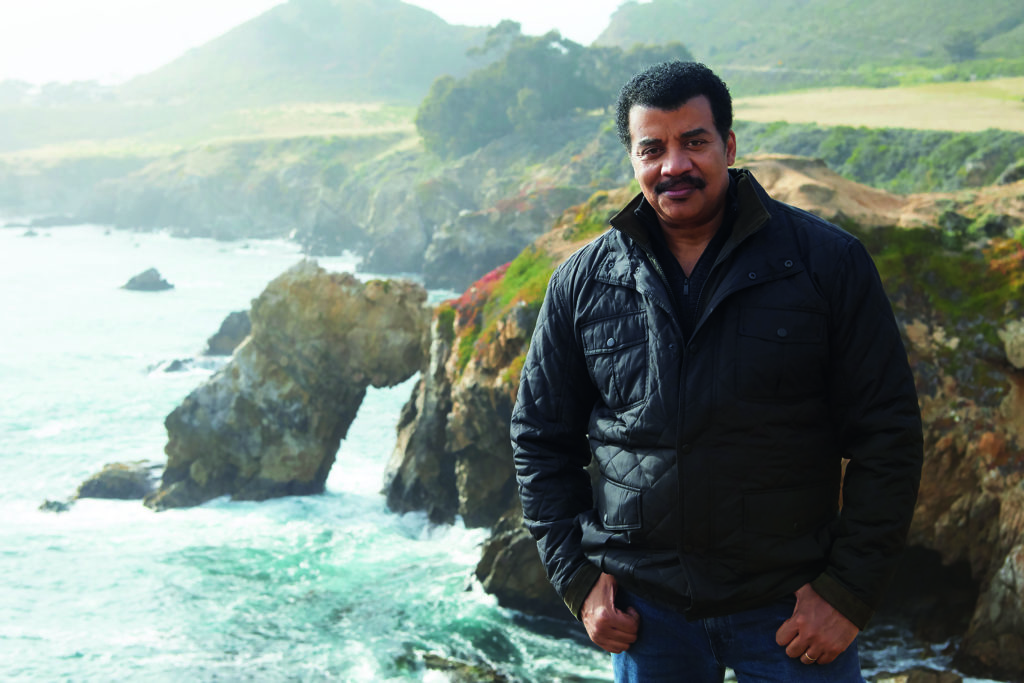

Life, Cosmos and Neil deGrasse Tyson

by Scott Dutfield · 15/10/2020

40 years since the original iconic series hit our television screens, Cosmos is back. We catch up with host Neil deGrasse Tyson about the new series

Astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson is the host of the Emmy-nominated StarTalk, a best-selling author and science communicator. Following in the footsteps of revered astrophysicist Carl Sagan, who pioneered the groundbreaking 1980 space documentary series Cosmos, Tyson takes audiences through the interconnectivity of our universe and life on Earth in a new and visually stunning 13-part series: Cosmos: Possible Worlds.

Is it true that we are all made of stardust?

One of the remarkable things about the universe is that the laws of physics that we measure here on Earth apply everywhere. This was not a given when we first started thinking about the universe as a place where laws apply. It not only applies on Earth, but on other planets, stars in other galaxies, and it applies throughout all time. As we look at outer space, we look back in time, and as we see things in the past, the laws of physics are manifesting in exactly the way they manifest in the present. Then we can ask, what are we made of? We’re made of these organic molecules containing atoms: carbon, nitrogen and oxygen and silicon. But where do these come from? I remember asking my chemistry teacher in high school where they came from, and she said “they’re in the Earth”, and that wasn’t satisfying enough to me. Then I studied more astrophysics, and learnt the origins of these elements are traceable to stars which manufacture these elements. These elements that we are comprised of are the most common elements in the universe. How innovative it is for the universe to take its most common ingredients and make something that can contemplate its own existence, which is what happened in at least one place in the universe, here on Earth. The notion that we are stardust is not only poetically accurate, but it’s actually literally true.

How have scientific discoveries made since 1980 influenced the new series?

That’s a great question because there are different ways I can splice it. I can splice it scientifically, but also culturally. Cosmos is a source of intellectual and cultural enlightenment. By the time you’re done watching it, you feel empowered by what you’ve just learned to do something about the civilisation in which we’re all embedded. From 1980, I can list all the scientific advances since then, but it’s not what matters as much to Cosmos. In 1980 we were still in the Cold War. There are some aspects of that program, given the idiocy of the world being held hostage by nuclear weapons. Right now we’re not in a Cold War, but we have other challenges. Back then, while scientists knew we were warming the planet, it was not yet public… the public had not really latched on to that reality. But of course, climate change has become an emerging existential threat that has occupied much of the attention of this third instalment of Cosmos. We talk about discoveries such as black holes in the centres of galaxies and exoplanets, but at the end of the day, Cosmos takes these discoveries and holds them up to you and says, given these discoveries, and newfound understanding, what is our place in the world and in the universe, and what are we going to do about our fate?

What surprised you the most during the making of Cosmos?

My expertise is astrophysics, but one of the fundamental elements of Cosmos’ DNA is the seamless blending of the branches of science. One of the great strengths of Cosmos is how nimble the narrative is in weaving through these different subjects. Some are quite challenging. Quantum physics is a topic, and there’s an episode where we go inside the atom. There were some challenges that I think we rose to. We have very creative people – set designers, visualisers – and they’re guided by the science and rose to that challenge. All of these become parts of the storytelling and the concept of Possible Worlds, even though the context is the universe because that’s your first thought.

You will learn in the series that a world doesn’t have to be a body in space. There’s this mycelium, an interconnected network underfoot which plants use to communicate with one another electrochemically. That’s a world. There’s an episode on the first occasion where brain waves were measured and the birth of neuroscience. Talk about a frontier. That’s a whole universe unto itself. Possible Worlds breaks our own ego and our own stereotype of what we think the world is. Our ego, in the sense that we think we’re the only ones communicating and who have a network of the internet, but the mycelium network predates the internet. It’s a way to achieve a new perspective on ourselves. Cosmos: Possible Worlds shows you worlds that were hidden in plain sight, as well as worlds in space.

What lesson can viewers learn from the show?

That science is an awesomely powerful tool to benefit us, but you don’t want it to benefit us in a way that disrupts the ecosystem that sustains us. It’s using wisdom and knowledge in the service of not only our own happiness and survival for the future, but as a way to thrive, and how do we without destroying the very thing that supports us in the first place? That takes inventive engineering and science. All of that is captured if not in one episode then in another across the season of Cosmos. It’s not preachy, but it’s there. Definitely, you come away wanting to become a participant in the solution, not simply an observer of it.

Cosmos: Possible Worlds is now available to watch on FOX

This article was originally published in How It Works issue 137

For more science and technology articles, pick up the latest copy of How It Works from all good retailers or from our website now. If you have a tablet or smartphone, you can also download the digital version onto your iOS or Android device. To make sure you never miss an issue of How It Works magazine, subscribe today!