Meet the Megasharks

by Scott Dutfield · 17/01/2019

As one of the world’s largest prehistoric predators, the mighty Megalodon could eat whales for breakfast

Deep beneath the surface of the Mediterranean, slicing through the open ocean, an iconic silhouette approaches a whale. In a flash it delivers a fatal strike, the whale helpless in the face of nearly 300 serrated teeth as a beast bigger than a bus closes its jaws like a vice. Meeting its end, the whale is but one of the many meals this megalodon will feast upon today. This would have been a regular occurrence around 20 million years ago. Today, whales, along with many other marine mammals, can swim without fear of a giant shark closing in on them with its titanic jaws.

A SHARK’S TALE

A mighty megalodon could make the modern-day great white shark its chew toy. It’s estimated that these beasts reached up to 18 metres in length and were armed with around 276 teeth. Carcharocles megalodon, as it’s formally known, is believed to have navigated the world’s oceans during the Neogene period. Megalodon literally translates as ‘big tooth’, and the species certainly lived up to its name: its teeth could grow up to 18 centimetres and were arranged in five separate rows. This, along with its sheer mass and bite force, made it the most deadly predator known to ever swim the seas. Its prestigious predatory status has made the megalodon a prehistoric sea monster that is frequently showcased in feature films, where it faces o against other gargantuan beasts. These fearsome fish will grace the big screen again this year in The Meg, which depicts the megalodon as a giant killing machine hell-bent on hunting down unsuspecting swimmers. In reality, the megalodon would have had bigger fish to fry than comparatively tiny humans. A megalodon would need to consume around a ton of food per day to maintain its 60-plus-ton weight, and on its mega menu were whales, seals and fish – including other sharks. And like other shark species, megalodons didn’t just feast on freshly caught prey; they were also scavengers. If the remains of another creature’s kill floated by, the megalodon was not one to turn its nose up at a free meal. The Mediterranean Sea wasn’t the only hunting region for these mega sharks; evidence of their predatory presence has been found across the globe’s warmer waters. From the coasts of North and South America to the far reaches of the Indian Ocean, during the megalodons’ prime, it dominated intercontinental waters as an apex predator. Back in 2010, a team of palaeontologists discovered a 10-million-year-old prehistoric shark nursery in Panama. Over 400 fossilised megalodon teeth were recovered, with most ranging between 1.6 to 7.2 centimetres in length. From these teeth, the researchers estimated that the young megalodons would have been between two and 10.5 metres long.

SHARK-TOOTHED COUSINS

It’s often said that modern-day great white sharks are smaller ‘living fossils’ of the once magnificent megalodon. Unfortunately, the palaeontologists trying to understand the truth about the great white’s heritage have limited resources available to them. The fossilised dental records of these mega sharks are scattered across the world, each fragment of tooth an indicator of a shark’s size, shape, diet and ancestry. Like modern-day sharks, a megalodon’s body was predominately rarely preserved in sediment over millennia, so we don’t find whole fossilised sharks in the same way we do dinosaurs. However, their centra (the main body of the vertebrae) can sometimes become calcified and preserved, leaving behind what looks like rocky hockey pucks. In a similar way as counting the rings of a tree, the layers in these centra can reveal the age of a megalodon at death. The biological biography formed from these tooth and spine samples allows palaeontologists to answer a question long debated in the scientific community: is the modern-day great white shark a direct descendant of the megalodon? It was previously believed that from megasharks came the great white, a conclusion based on their dental duality. However, in recent years some palaeontologists have proposed another theory: that great whites descend from an ancient mako shark, and the two evolved side by side. The megalodon itself descended from enormous prehistoric sharks such as the otodus, a near ten-metre-long fish that dominated the oceans 50 million years ago. Both great whites and megalodons do share common ancestry, originating from a group of fish called Lamniformes, or mackerel sharks, as they are also commonly known. As the first shark-like creatures, Lamniformes began their evolutionary journey around 65 million years ago, diversifying and developing along the way into the sharp-toothed species we see today.

THE MEGA EXTINCTION

As invincible as they may appear at the box office, the megalodon could not fight o the forces of mother nature. The demise of these behemoths around 2.6 million years ago is believed to have been the result of several contributing factors. As climatic temperatures became cooler, megalodons moved to warmer waters to hunt and reproduce. However, their prey species – such as primitive baleen whales – were moving away from tropical waters, thereby reducing the availability of food. It has also been suggested that megalodons faced competition from the ancient ancestors of the killer whale, which were able to sustain themselves on smaller prey due to their smaller size. As mammals, these whales were also able to store fat and energy in blubber, giving them an extra advantage. As competition for food from growing whale populations increased, megalodons may have simply starved to death. Although the megalodon may have been wiped from the face of the planet, our fascination with this ferocious fish has not gone extinct. There are those who believe this beast is still lurking in the ocean depths, and some have even claimed to have spotted them. In his 1963 book, Sharks and Rays of Australian Seas, Australian naturalist David Stead relayed a tale from a group of fishermen who in 1918 claimed to have seen a gigantic shark that could only be compared to a megalodon. However, this claim, along with the many others that followed, remains unproven. The story of a living megalodon remains a fishy fairytale. Even so, our oceans are still vastly unexplored, with 95 per cent yet to be studied. Maybe somewhere in the depths of one of the world’s oceans there really is a whale about to meet its maker at the jaws of this mega-predator.

BIZARRE BITES

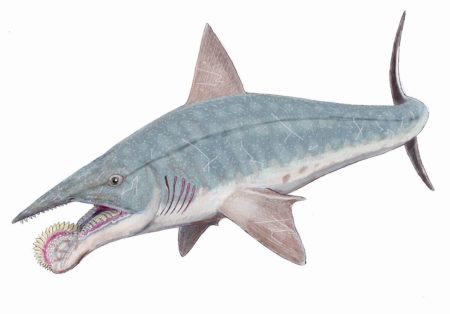

The megalodon was just one of many prehistoric predators whose appearance was more like something from science fiction than reality. The evolution of marine species over time has produced some truly weird and wonderful predators. The helicoprion (‘spiral tooth’) and edestus (‘scissor tooth’), for example, were a pair of fish that really diversified the aesthetics of marine predators with their bizarre arrangements of teeth.The helicoprion presented its teeth as a central arch in its lower jaw, whereas the mouth of the edestus housed two rows of centralised interlocking teeth. Cruising through the ancient oceans 270 million years ago, this dangerous duo weren’t strictly sharks – both instead classified as chimaeras, or ratfish – although they do bear a striking resemblance.

The helicoprion’s ‘whorl’ (or spiral) of teeth allowed it to cut through soft prey such as squid

This article was originally published in How It Works issue 114

For more science and technology articles, pick up the latest copy of How It Works from all good retailers or from our website now. If you have a tablet or smartphone, you can also download the digital version onto your iOS or Android device. To make sure you never miss an issue of How It Works magazine, subscribe today!