Why do some animals live together?

by Scott Dutfield · 14/05/2020

Different organisms can benefit from living with each other – but is it always a fair deal?

Lurking in the muddy waters of the River Nile, a crocodile carefully balances its eyes and snout above the surface. On the riverbank, a plover bird pecks at the ground.

Eyes trained on the feathered body, the crocodile paddles towards the unsuspecting plover before leaving the water and mounting the bank. With the crocodile’s mouth now fully open, revealing the razor teeth within, the plover rushes over as if to greet the giant reptile. Rather than fear for its life, it begins to peck at the gaps between the crocodile’s teeth, collecting ticks and debris as it goes. Undisturbed by this feathered flossing, the crocodile patiently waits for the plover to finish.

Each benefiting from the removal of parasitic pests, this reptile-bird interaction is a classic example of a symbiotic relationship. On a ‘scratch my back and I’ll scratch yours’ basis, many symbiotic relationships in nature can be beneficial for both animals concerned. However, not every partnership is equal.

The principle of ‘symbiosis’ was first outlined to describe lichen, a plant-like organism that consists of both a fungus and algae. It was then later applied to different animals that lived in mutually beneficial relationships, and has since expanded to include three different types of relationship: mutualistic, commensalistic and parasitic. Each category describes varying levels of beneficial behaviour and interaction.

When two organisms both benefit from a relationship, it is known as mutualism. Benefits of having a buddy in the animal kingdom typically centre around food, protection and transport. Where one animal, such as the Egyptian plover, benefits from a tasty meal, the other benefits from the removal of parasites.

Examples of symbiosis in this form abound in the animal kingdom. For example, in the shallows of the Pacific a crustacean and sea anemones come together to form the sea’s only cheerleading crab. Often called the pom-pom crab or boxer crab, this high-spirited critter swipes two anemones from the seabed and holds them in its claws. Known for their stinging ability, they offer the crab protection and a new way to catch food, while the anemones gets a free ride to feed on organisms. The same principle applies to many different forms of marine life, such as the relationship between clownfish and anemones.

Above the ocean waves, examples of mutualism can be found across the world, from the oxpecker bird tackling the ticks dwelling in zebra ears to the hunting partnership of coyotes and badgers. However, one of the most abundant forms of mutualism comes in a global partnership between plants and animals: pollination. Here, a species of bird, mammal or insect feasts on the nectar of plants, while brushing up against the plant’s pollen or seeds, which are then dispersed by the animal when it moves on. By visiting many flowers, bees introduce pollen and fertilise plants on their nectar-gathering journey, while deer might disperse seeds in their dung after feasting on nutritional fruit.

There are, however, relationships in which only one animal benefits from interacting with another, known as commensalism. It’s a one-sided deal, but the species will take advantage of another without causing them any harm. On the underbelly of a whale shark, there are often several long fish hitching a ride. These marine hitchhikers are called remoras, and thanks to a specially modified dorsal fin they can stick to larger fish for easy travel. Equipped with tiny, harmless spindles, this suction cup fin creates enough friction to adhere to a scaly surface. By slightly changing the fin’s shape, a remora can quickly detach. Without any benefit to the shark, remoras not only conserve energy, but after a shark has torn apart its prey, they can scavenge the floating debris.

Golden jackals that have been expelled from their pack have also been witnessed to follow another species’ movements to benefit themselves. Hot on the heels of a tiger, these jackals will stalk big cats in the hope of feasting on the remains of their latest kill. Undisturbed by the shadowing jackal, the tiger neither benefits from nor is hindered by its activity, whereas the jackal might get a quick and easy meal from the tiger.

In parasitism, however, one organism in this symbiotic relationship benefits at the expense of the other. The origin of the word parasitism means ‘one who eats at the table of another’ – an appropriate description as most parasites are blood-suckers or nutrient vampires. Often stealing just enough to feed themselves, parasites feast without completely killing their hosts. Ticks and fleas, for example, live on their host’s skin or nestled between their hairs, drinking the warm blood of their host mammal. Although just a few drops are more than enough to keep these tiny organisms alive, they pose an infection risk from the bacteria that they can transmit.

Some parasites work from the inside out, such as tapeworms. Once ingested as larvae, these spineless worms grow within the bowels of their host, feasting on the digesting food and even the surrounding tissue.

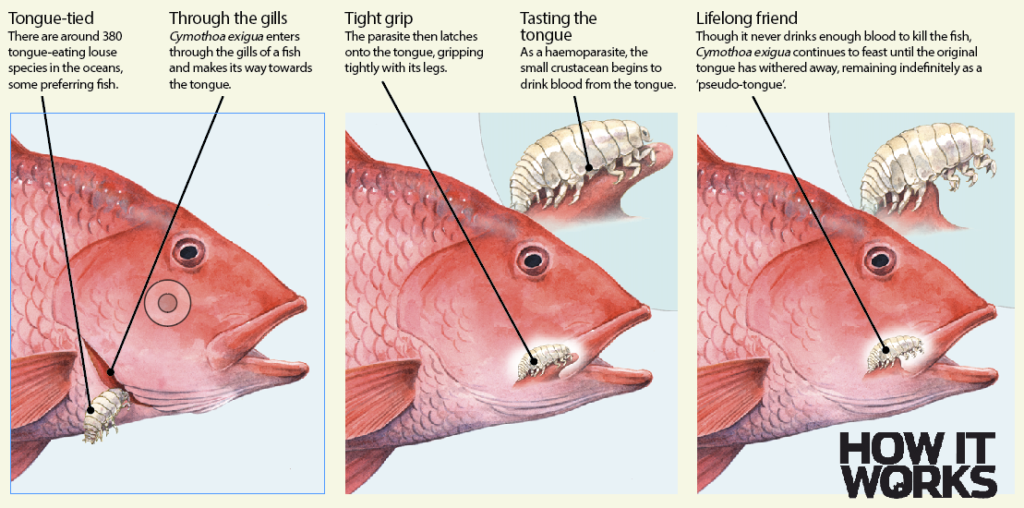

However, to ensure their position as a parasite, there are those that have evolved to become a physical part of their host. Hiding in the jaws of its fishy victims, the tongue-eating louse, a small marine arthropod, slowly replaces the tongue of its host fish, where it remains indefinitely. This parasite takes exploitation to a horrifying new level – in 2014, it gave one British man a fright when he discovered a set of eyes staring at him from inside the mouth of a sea bass he’d freshly purchased from his local supermarket.

Crustacean got your tongue?

Discover how this tongue-eating louse replaces its host’s tongue

This article was originally published in How It Works issue 130;

For more science and technology articles, pick up the latest copy of How It Works from all good retailers or from our website now. If you have a tablet or smartphone, you can also download the digital version onto your iOS or Android device. To make sure you never miss an issue of How It Works magazine, subscribe today!