7 Environment Myths Busted

We unravel some common misconceptions about the natural world

1. “HUMANS EVOLVED FROM CHIMPANZEES”

Although there are similarities between humans and chimpanzees, such as opposable thumbs and facial features, but chimps didn’t just shed their fur and start making fi res. We are, however, genetically related to chimps through our common ancestors, along with other great apes like gorillas and bonobos. The first sign of primates on Earth dates back to around 55 million years ago (MYA). Then, from a common ancestor, chimps and humans split into two distinct genetic timelines between 8–6 MYA, although a more recent study suggests that divergence may have occurred up to 13 MYA. Our primate cousins continued to evolve into the apes we see today, whereas others evolved into the group known as Hominini, of which we are the only surviving species. Chimpanzees remained in the group Hominoidea, which divides over 20 species between great apes such as orangutans and lesser apes such as gibbons. It was around 5.8 MYA that one of our proposed ancestors — Orrorin tugenensis — walked on two legs, despite closely resembling a chimpanzee. About 4 MYA, our prehistoric species developed a brain more representative of the Homo sapiens we are today — these more advanced ancestors were Australopithecus afarensis. Our use of tools dates back some 2.6 MYA, regularly used by Homo habilis and Homo erectus, who around 1.8 MYA, was the fi rst to stand up straight. Though we started our evolutionary journey together, chimps and humans evolved alongside one another rather than us descending from them.

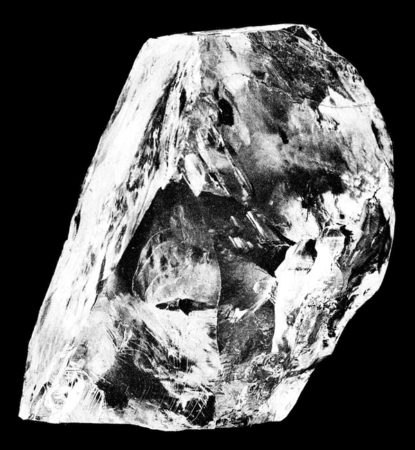

2. “DIAMONDS ARE MADE FROM COAL”

It is often thought that diamonds form from the compression of coal, but these beautiful gems originate from a deeper geology. The confusion comes from their similarly high content of carbon. Both diamonds and coal are made of carbon, but they form in di fferent layers within the Earth. Diamonds form in the Earth’s mantle, around 145 kilometres below the surface. At temperatures of around 1,050 degrees Celsius, diamonds form from carbon under the immense pressure of the Earth’s mantle. Ejected via volcanic eruptions, diamonds are pushed to the surface, hitching a ride on a magma channel rising from the mantle. Diamonds have also been known to come from the subduction zone, where an oceanic plate collides with a continental plate, forcing the oceanic plate underneath its continental counterpart. This process occurs at a lower temperature and pressure, so smaller diamonds are formed. On the other hand, like a sedimentary rock, coal is the product of the decomposition of natural materials such as sea life and plant material. Coal is formed much higher up in the mantle and is rarely buried to depths greater than 3.2 kilometres. Though it would make a great rags to riches story, in the case of diamonds, it’s riches all the way. The word ‘diamond’ is derived from the Greek word ‘adamas’, meaning invincible or indestructible Once cut and polished, diamonds present their unique sparkle.

3. “CAMELS’ HUMPS ARE FILLED WITH WATER”

In order to survive the intense heat of the desert climate, one or two giant biological water bottles sounds like a great idea. But the idea of a camels’ hydrating humps are just a myth, but a myth not far from the truth. Rather than being filled with water, camels’ humps are filled with fat. Similar to the lack of water, deserts aren’t known for their lush green vegetation. These mobile mounds of fat stores offer energy for camels to make use of when food is scarce. The longer the time between meals, the more deflated these humps appear as their resources are being used up. This isn’t to say that camels don’t consume a lot of water; they just don’t store it in their humps. When arriving at a watery oasis, the two-humped Bactrian camel, for example, can drink over 100 litres of water in one go. But, camels do have biological adaptations to optimise water storage. For example, camels’ faeces is dry, they have little urine output and are able to fluctuate their body temperature to reduce levels of sweat. So, while their humps aren’t filled with water, they have made the changes needed to survive in the harsh climate of the desert.

4. “CLOUDS ARE LIGHTWEIGHT”

Like cotton wool, clouds are always used to describe the lighter things in life. But while they may glide gracefully around a blue sky, clouds are the heavyweight giants of our atmosphere. When you consider the amount of water that comes from a massive downpour, imagine how heavy the cloud must have been to hold it. The water density of an average fluffy cumulus cloud is about 0.5 grams per cubic metre. If you propose a cloud that is one kilometre long, tall and wide, that gives you a total of 1 billion cubic metres in volume. That works out at around 500 tons of water — the same as around two and half blue whales floating above our heads! This method also suggests that larger and denser cumulonimbus clouds could weigh around 1 million tons! It’s a huge weight, but the surrounding atmosphere is denser than the cloud, so it floats. Temperature also plays a part in keeping these clouds in the air, as warmer air is less dense than cool. As we know, when a cloud gets too full of water, droplets form and we get rain, and the weight of the cloud reduces as a result. So next time it’s a cloudy day and pouring it down, there could be literally tons of water falling over your head.

5. “BANANAS ARE A FRUIT”

It’s another ‘is a tomato a fruit or a vegetable?’ debate. Botanically, a fruit is defi ned as a seed-bearing structure that develops from the fl owering plants of a woody tree or bush. The evolutionary purpose for this structure is to entice animals to eat the juicy sweet or sour fruit, helping to spread the seeds in their waste, thereby helping plants reproduce. The humble banana, however, does not encapsulate its seeds around a fl eshy fruit. Instead, the small black seeds (the little dots in the middle) are within the banana’s fl esh, making it more of a berry, which they would be classifi ed as if their seeds were fertile. Since bananas have been commercially grown the seeds do not mature, and the ‘tree’ a banana grows on doesn’t contain true woody tissue, making them a simple herb.

6. “GOLDFISH HAVE THREE-SECOND MEMORIES”

‘You’ve got the memory of a goldfish’ is something often heard over your shoulder while you’re hunting for a bundle of misplaced keys. This myth began when humans decided to take these orange iridescent fish as pets. Some think that the myth originated as a justification for keeping fish in small tanks. By the time they had done one lap of the bowl it would be a new experience going around the second, then the third time, and so on. However, studies have shown this to be untrue. Research has revealed that goldfish can remember food locations and even the people who feed them. Just think, when you go to feed your goldfish, do they come up to greet you? One study by The Technion – Israel Institute of Technology conducted a fascinating study to test out this myth. The research team trained captive fish to associate a particular sound with that of feeding time. They continued this for a month before releasing them into the wild. The fish were left in the wild for five months, the sound was then played again and the fish that remembered the association between the sound and food came back. So the next time you lose your keys, try asking the goldfish.

7. “LIGHTNING NEVER STRIKES IN THE SAME PLACE TWICE”

It’s a common myth that if you stand where a lightning bolt just struck then you’re safe. It appears that probability is the driving force behind this potentially dangerous myth, but there is a higher chance to be struck twice than you’d think. In order for a lightning bolt to hit the ground, a discharge of pent up electrical energy within the cloud travels through ionised air. In a matter of milliseconds, the strike reverberates, meaning multiple strikes occur during what appears to be a singular event. As this is a cloud-to-ground event, the closer objects on the Earth’s surface are to the cloud, the more likely they are to be struck. Take the Empire State Building, for example, which gets hit an average of 23 times a year. Fortunately, it is equipped with lightning rods to help ground the charge in order to keep everyone inside safe.

This article was originally published in How It Works issue 108

For more science and technology articles, pick up the latest copy of How It Works from all good retailers or from our website now. If you have a tablet or smartphone, you can also download the digital version onto your iOS or Android device. To make sure you never miss an issue of How It Works magazine, subscribe today!