7 Creepy worlds across the cosmos

by Scott Dutfield · 28/10/2020

The universe is a weird and wonderful place, but some of the strange new worlds we’ve discovered are far from welcoming…

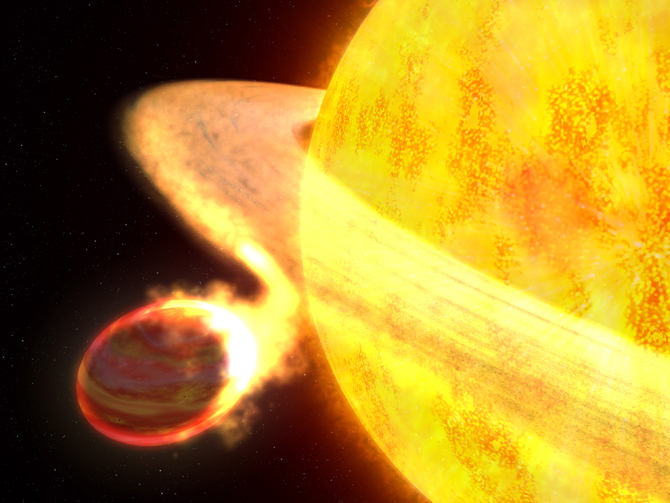

Doomed planet

Planet: Wasp-12b

Discovered: 2008

Distance from Earth: 1,400 lightyears

Similar to TrES-2b, Wasp-12b is another hot, Jupiter-like world that reflects very little light. If this wasn’t bad enough, the planet itself is slowly being ‘eaten’ as its atmosphere is escaping into the grasp of its parent star. It’s estimated that Wasp-12b will be fully consumed within the next 10 million years.

Image credit: NASA/ESA/G. Bacon

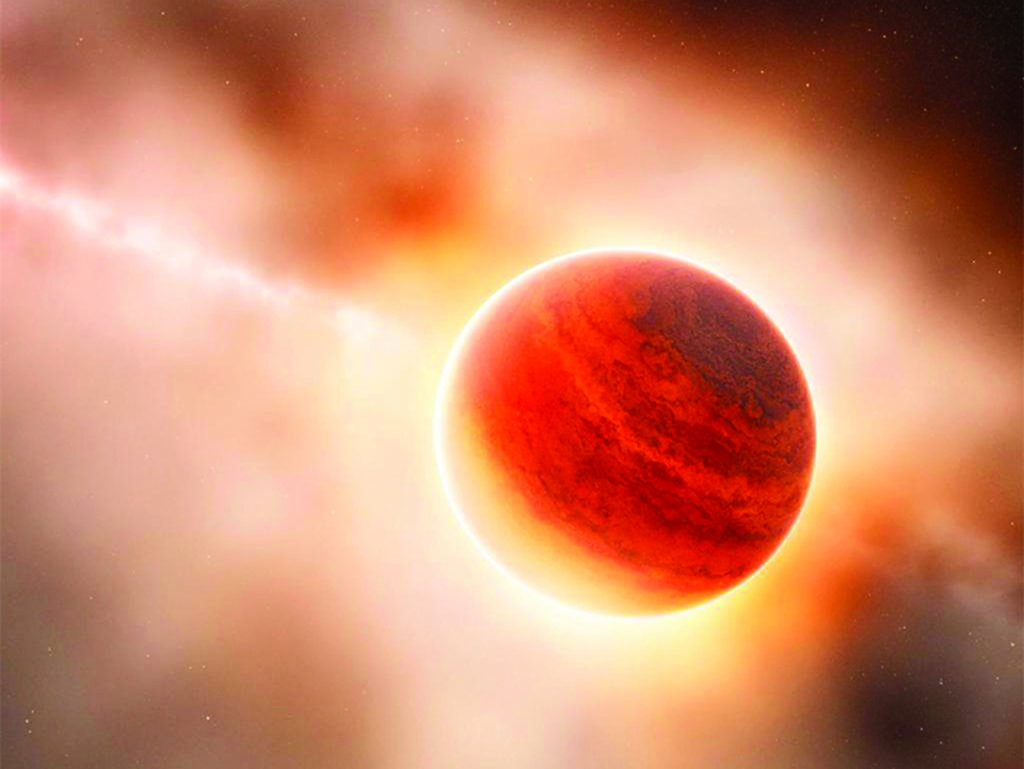

Burned alive

Planet: Kepler-70b

Discovered: 2011

Distance from Earth: 4,200 lightyears

It is thought that this rocky world used to be a gas giant like Jupiter until it was engulfed by its star. Kepler-70 expanded into a red giant, swallowing the surrounding planets and spitting them back out again as it shrank to its current sub-dwarf form. The planets survived, but taking a trip into a star did not leave them unscathed. Kepler-70b’s rocky form is all that remains after its gaseous atmosphere was vaporised. It’s also the hottest exoplanet ever discovered, with temperatures estimated at around 6,800 degrees Celsius.

Image credit: NASA

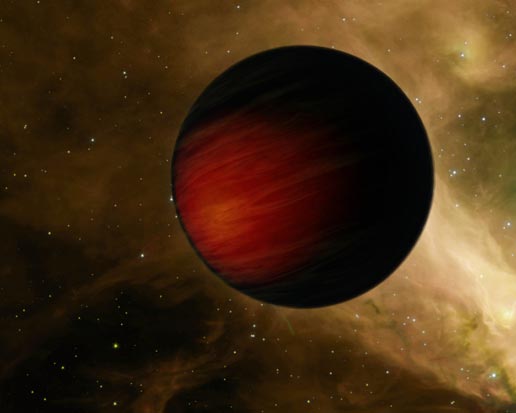

Eternal darkness

Planet: TrES-2b

Discovered: 2006

Distance from Earth: 750 lightyears

This alien gas giant reflects less than one per cent of the sunlight that falls on it, making it blacker than coal and the darkest known exoplanet. It orbits just 4.8 million kilometres from its parent star, heating its atmosphere to over 980 degrees Celsius – too hot for reflective clouds like those on Jupiter to exist. Instead, its atmosphere consists of light-absorbing chemicals like titanium oxide gas and vaporised sodium and potassium.

Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Iron skies

Planet: KELT-9b

Discovered: 2017

Distance from Earth: 615 lightyears

KELT-9b holds the record for being the hottest known gas giant discovered so far. It’s so hot in fact that the term ‘hot Jupiter’ wouldn’t do it justice – instead, it is classed as an ‘ultrahot Jupiter’. It reaches temperatures of over 4,300 degrees Celsius as it orbits its extremely hot, young blue star.

Analysis of KELT-9b’s spectral data revealed that its superheated atmosphere contains iron and titanium atoms. While these elements are common, they are usually present within other molecules. On KELT-9b it’s too hot for clouds to condense, so these metals can exist alone.

Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

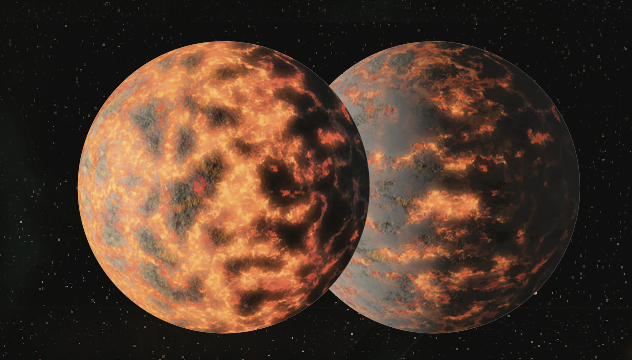

Two-faced super-Earth

Planet: 55 Cancri e

Discovered: 2004

Distance from Earth: 40 lightyears

This weird world is tidally locked to its star, meaning one side is in permanent daylight while the other experiences a never-ending night. The day side averages temperatures of over 2,300 degrees Celsius, while the cooler night side is ‘just’ around 1,300 degrees. Observations from the Spitzer telescope originally indicated that this may be a lava world covered in moulten rock that flowed on the light side and solidified on the dark side. However, more recent analysis suggests it probably has a thick atmosphere, which may or may not be hiding lava lakes below.

Image credit: NASA

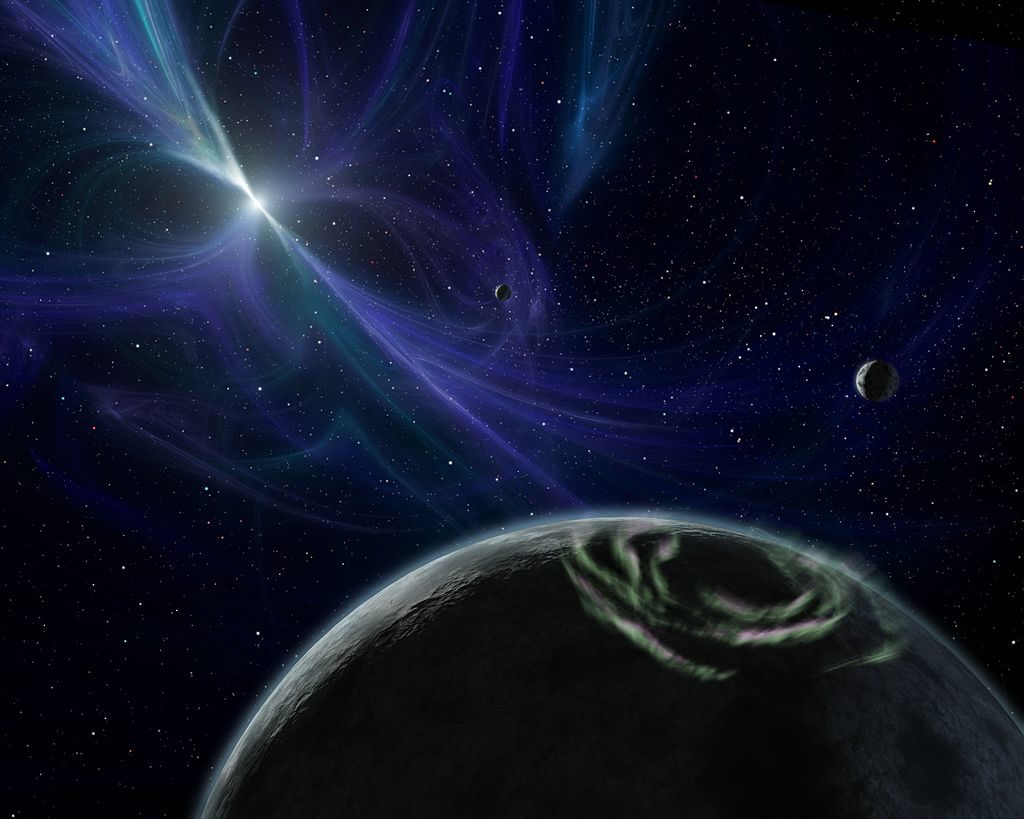

Radioactive graveyard

Planet: Draugr, Poltergeist and Phobetor

(PSR 1257+12 b, c and d)

Discovered: 1992–1994

Distance from Earth: 2,300 lightyears

PSR 1257+12 b, c and d was the first confirmed exoplanet system to be discovered, but any hopes of them being habitable were well and truly dashed. They are in orbit around a pulsar – the collapsed core of a star that forms after a supernova. The dramatic stellar explosion would have stripped the planets of any atmosphere or life that may have existed upon them, and the remnant ‘corpse star’ pulsar now bathes them in intense, deadly radiation.

Image credit: NASA

Deadly rain

Planet: HD 189733 b

Discovered: 2005

Distance from Earth: 63 lightyears

If the barefoot scene from Die Hard makes you wince, you wouldn’t like life on this exoplanet. It rains shards of glass in over 7,000-kilometre-per-hour winds. This world may be blue like ours, but it’s nothing like Earth. Its colour comes from silicate particles condensing into glass in the superheated atmosphere. These glass raindrops scatter more blue light than red, resulting in swirls of cobalt clouds.

Image credit: NASA/ESA/m kornmesser

This article was originally published in How It Works issue 117, written by Jackie Snowden

For more science and technology articles, pick up the latest copy of How It Works from all good retailers or from our website now. If you have a tablet or smartphone, you can also download the digital version onto your iOS or Android device. To make sure you never miss an issue of How It Works magazine, subscribe today!