Why does Africa need lions?

by Ailsa Harvey · 22/05/2020

Meet the king of the jungle and discover how his kingdom has changed over time

(Image source: Pixabay)

Prowling across the African savannah, the ‘king of the jungle’ has gained a reputation as a fierce, formidable predator, not to be trifled with. As keen killers, lions have evolved to form social hunting packs called a pride. This feline squad is typically comprised of 14 members, but prides as large as 40 individuals have been reported.

This social structure is made up predominantly of females, with one of two males for reproduction and protection from other wandering males. Lionesses in a pride are typically related and spend their entire lives with their family, but for males reaching the age of three, the time comes to leave the pride and search for a new home.

As unrivalled predators, these food-chaintoppers work as a team to take down prey across the African plains. From agile antelopes to thunderous elephants, lions and lionesses bide their time, stalking within the savannah’s tall grass before pouncing on their prey.

Lions play a vital role in the ecology of Africa’s wildlife. Much more than charismatic attractions for onlooking tourists, lions help maintain the environment by managing those that cause it damage. Similar to any large carnivore, lions help to control the populations of many herbivore species, such as antelopes and zebras. These grass-grazing species have the potential to disturb the natural balance of an ecosystem by overgrazing. Therefore, apex predators – those at the top of the food chain keep populations from growing too big by using them as a food source.

Lions tend to prey on the weakest and slowest in the herbivorous herd. The individuals falling behind are often suffering from natural disease. By removing these infected individuals, the herd is spared from the disease spreading, so lions can act as a defence against disease.

A world without large carnivores like the lion would also see the rise of a new food chain in which medium-sized predators take centre stage. Lions not only feed on these predators but also compete with them for food resources and territories. Should lions be removed from Africa then these predators, such as the wild dog, would be free to grow in numbers, and their prey species would decline. Unable to tackle African giants like buffalo and giraffes, the dynamics of the African ecosystem would completely change.

This is known as ‘mesopredator release’ and can have a devastating effect on biodiversity. As the linchpin of African wildlife, lions are often referred to as a keystone species, where without them some ecosystems would unravel. Unfortunately, over the past few decades these majestic mammals have become vulnerable to eradication in Africa. Having once stretched their paws across the entire continent, lions are now restricted to small pockets of territory across central and southern Africa. It is estimated that there are 23,000 to 39,000 individuals left in the wild.

(Image source: Pixabay)

Threats to lions

The main threat to a lion pride is the use of land in their territories for farming and urbanisation. Also, due to the overhunting of prey species, some lion prides have been starved into extinction or forced to migrate to other areas, where they might come across farmers who are trying to protect their livestock – their entire livelihood – and meet their demise at the end of a gun.

Alongside conflict with humans, use of industrial poisons across African countries has also been the cause of many lion deaths. Although the lion has faced hardships over the years, there are ways in which the species can be kept from the brink of extinction. In order for lions to thrive in the wild they require a great deal of space to hunt. The typical territory of a pride is around 260 square kilometres. Therefore, in order to keep these big cats safe, national parks and sanctuaries have been set up across Africa to prevent illegal poaching. The areas are often solely protected by legal designation, but some countries actively secure borders with fencing or human patrols. Ruaha National Park in Tanzania holds around ten per cent of the world’s remaining lion population. Working with local communities, the park’s representatives have been developing lion-proof enclosures to house livestock, in order to reduce the retaliative killings of lions by farmers.

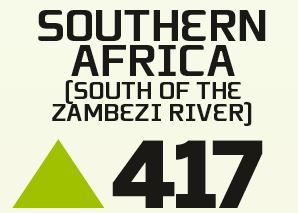

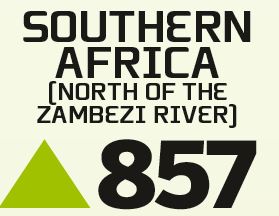

Population change between 1993-2014:

This article was originally published in How It Works issue 128, written by Scott Dutfield

For more science and technology articles, pick up the latest copy of How It Works from all good retailers or from our website now. If you have a tablet or smartphone, you can also download the digital version onto your iOS or Android device. To make sure you never miss an issue of How It Works magazine, subscribe today!