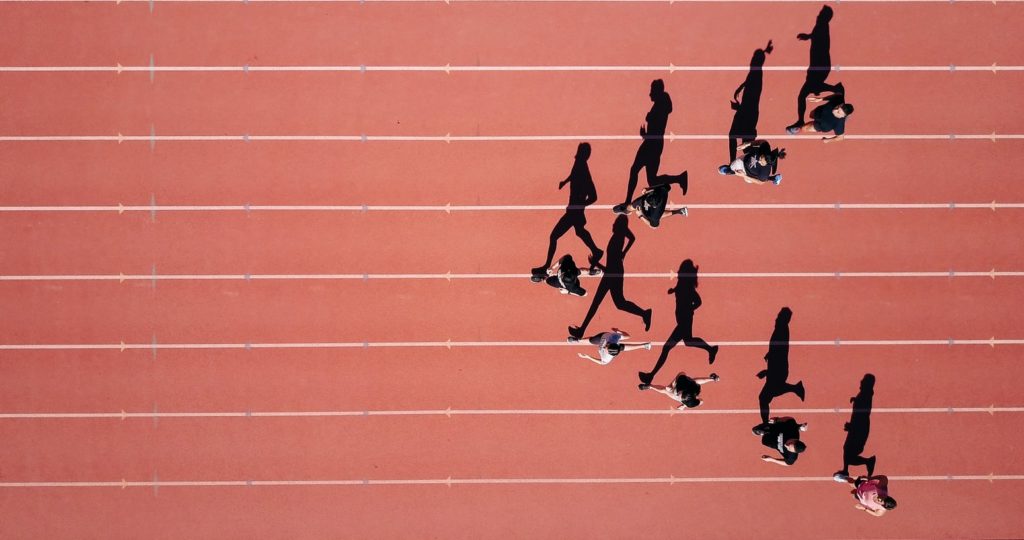

A history of doping in sport

by Ailsa Harvey · 17/06/2020

Uncover the methods some athletes have used to cheat their sport and how science has risen to stop them

(Image credit: Steven Lelham)

In 1954, physician John Ziegler was meeting with a colleague from the Soviet Union. Both scientists were in the employ of their respective country’s weightlifting teams, and at that moment in time the Soviets were ahead. They were just too strong. Ziegler pressed for an explanation, and his Soviet counterpart offered him one – his team had been using testosterone to build muscle mass, and the results spoke for themselves.

Anabolic steroids had not yet been banned in professional competition, so Ziegler swiftly returned to his team and shared his discovery. Soon the US team, like the Soviets, were pumped full of doping agents. This was an arms race in a very literal sense. But the US and the Soviet Union weren’t the only two players. All over the world, in different sports, athletes turned to drugs to enhance their performance. The tide of doping would lead to one cyclist saying that all he had to do was “follow the trail of empty syringes and dope wrappers” to stay with the pack during a race. Natural prowess had been shunned for artificial gains. The anti-doping agencies had to fight back; they needed new tests, and quickly.

Luckily the tests arrived. Today, the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) uses around 30 state-of-the-art laboratories that are equipped to screen for hundreds of doping compounds. They’re able to detect anabolic steroids, stimulants, diuretics, narcotics, alcohol, synthetic oxygen carriers and more. From ancient tricks through to today’s drugs, this timeline shows how anti-doping has evolved.

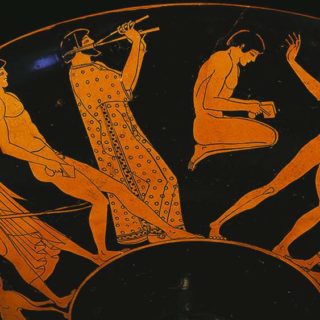

c. 700 BCE

At the ancient Greek Olympic Games, athletes are encouraged to consume sheep testicles, which contain testosterone, as a means of boosting strength.

(Image source: Antikenmuseum)

1904

Marathon-runner Thomas Hicks receives two injections containing the stimulant strychnine (plus some brandy) from his trainer during the race itself. Although extremely dangerous, he goes on to take home the gold.

1928

The International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) becomes the first sporting body to ban the use of doping agents for enhancing performance. The IAAF, however, is limited in its ability to enforce the new ruling. Instead it relies mostly on an honesty policy from athletes.

(Image source: AxG)

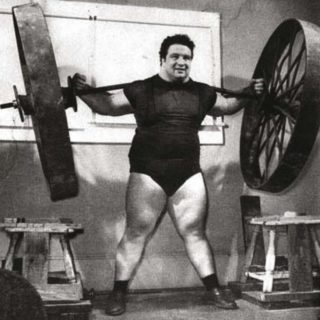

1954

A physician for the US weightlifting team learns that the Soviet Union team has been using testosterone to boost performance. The US team begins using anabolic steroids soon after.

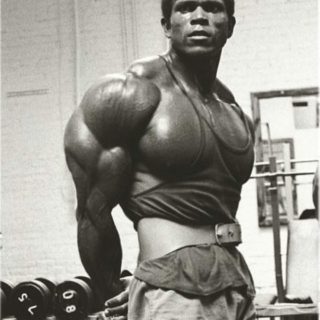

(Image source: Vecchio giornale di body building)

1960

Danish cyclist Knud Enemark Jensen dies during the Rome Olympic Games after taking amphetamine – a stimulant – and Roniacol, a blood vessel dilator.

1964

Anabolic steroid use becomes ubiquitous at the Olympic Games and in other sports, including bodybuilding.

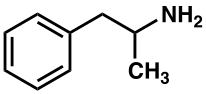

(Image source: Richyep)

1966

Drug testing begins for the first time at the European Athletics Championships, held in Budapest, Hungary.

1976

The first test to reliably detect anabolic steroids is developed, enabling governing bodies to ban these substances in future Olympic Games.

1988

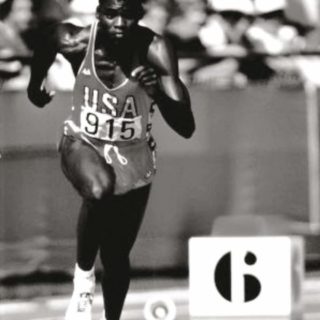

100m sprint Olympic champion Ben Johnson is stripped of his gold medal for doping. His prize is handed over to runner-up Carl Lewis, who keeps the medal despite also failing a drug test.

Pictured: Carl Lewis (Image source: KUHT)

2009

The Athlete Biological Passport programme is launched. An athlete’s biological marker information can now be tracked over time, allowing investigators to spot the introduction of doping agents.

2012

Seven-time Tour de France-winning cyclist Lance Armstrong is stripped of all titles received since 1998 after drug and blood doping.

(Image source: Hase)

2015

Russian athletes are banned from international competitions after evidence emerges of state-sponsored doping cover-ups.

(Image source: Pixabay)

2020

As tackling the global pandemic COVID-19 becomes priority, anti-doping testing is reduced. In Germany up to 95% of these tests are stopped. With plans to return to catching out dopers, the UK anti-doping chief reveals alternative methods to monitor those ordering performance-enhancing drugs during lockdown.

This article was originally published in How It Works issue 129, written by James Horton

For more science and technology articles, pick up the latest copy of How It Works from all good retailers or from our website now. If you have a tablet or smartphone, you can also download the digital version onto your iOS or Android device. To make sure you never miss an issue of How It Works magazine, subscribe today!