Da Vinci’s amazing notebook

by Scott Dutfield · 15/01/2020

Flick through the pages of the original Renaissance man’s greatest scientific studies

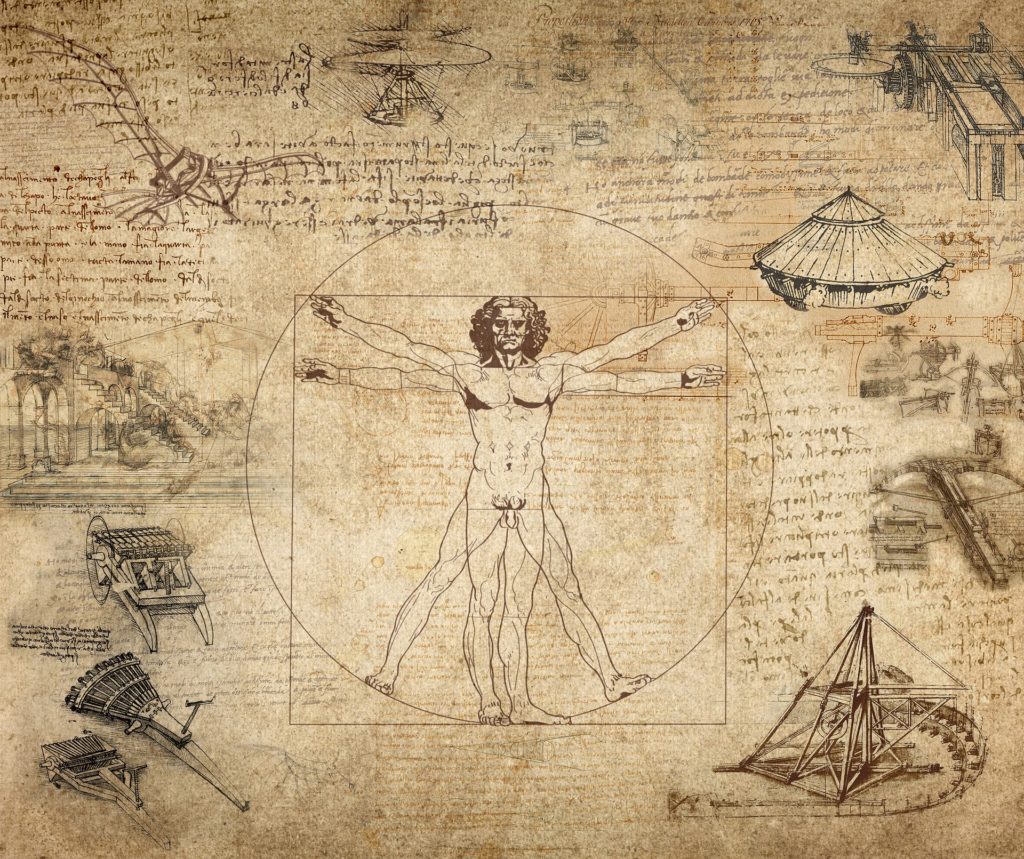

Born in 1452 in Tuscany, Leonardo da Vinci spent his life in the pursuit of knowledge and artistic expression. Now revered for his great works of art, such as the Mona Lisa and Salvator Mundi, da Vinci’s scientific notes suggest his thinking was hundreds of years ahead of his time.

He filled countless notebooks during his career, each bursting with observations about the natural world, the human body and numerous mechanical inventions. One collection in particular, the Codex Atlanticus, spans 12 volumes and includes 1,750 drawings.

One of the main focuses in his engineering endeavours, the concept of putting a man in the sky, piqued his interest, and a string of flying machine designs followed. One of his drawings details the design for an ‘aerial screw’. Appearing as the ancestor of the modern-day helicopter, this machine was designed to test the air’s ability to compress and support human travel in the air. The aerial screw was one of many flying machines conceived by da Vinci, including one that replicated the flapping wings of a bird, but none were made in his time.

Designing multiple other engineering concepts, including weapons, theatrical equipment and hydraulic machines, da Vinci’s notes are an inspiration.

Leonardo da Vinci is also well known for the study of the human body – both outside and inside. Around the 1480s his attention turned to the study of human anatomy to better understand the subjects of his art. From the structure of a single hand to the entire circulatory system, da Vinci studied the body in its entirety. His anatomical studies mainly used animal subjects, though by the time of his death he had also performed 30 or so human dissections, mostly using executed criminals and unclaimed bodies.

Seen in his surviving notes and anatomical drawings, da Vinci made waves with his near-accurate description of the human heart. Creating a glass heart from that of an ox, da Vinci not only noted its appearance but put his theory of its function to the test. By pumping water through the glass da Vinci deduced that there were vortices (a strong movement of blood) in the heart’s chambers. This motion was responsible for the closure of the heart’s valves after each pump of blood. It wasn’t until the introduction of real-time MRI scanners that da Vinci’s work was confirmed as accurate.

“Had he not done anything else in his career, had he not painted a single thing, this would have still marked him out as being one of the great figures of the Renaissance, certainly one of the greatest scientists, both in the depth and the range of his work on human anatomy,” said Martin Clayton, head of prints and drawings for Royal Collection Trust at Windsor Castle, and a specialist in the drawings of Leonardo da Vinci.

Da Vinci’s scientific studies, however, didn’t always bear the fruit of scientific discovery and left him still scratching his head. In the later years of his career, da Vinci’s notes turned to the movement of water. He thought that by observing water he could understand the basis of force and movement. His extensive notes on the subject of water worked to codify its movement and interactions with the air. He drew the eddies and the circular motions that occur when water pours into a pool, for example.

However, unlike his engineering and anatomical work, this study highlighted some of the fundamental difficulties da Vinci faced. “Leonardo as a scientist finds it very difficult to move from the specific to the general,” notes Martin Clayton. “His scientific observations tend to restate endless specific examples rather than overarching principles. That is one of his downfalls as a scientist”.

Making a heart of glass

In order to study the inner workings of the human heart da Vinci created a glass model to test his theories

© Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

Seeing the invisible

Over time the work of da Vinci, like that of many other artists, is vulnerable to damage from the light, atmospheric or physical erosion. However, with the help of ultraviolet (UV) light previously unseen work is brought back to life. This was the case with a set of hand drawings da Vinci had completed as studies for his painting Adoration of the Magi. Invisible to the naked eye, these seemingly blank pieces of paper revealed the illustration when illuminated with UV light. This was due to the type of ink da Vinci usually used. Under UV light certain materials, such as paper, luminesce (glow). The iron-rich ink, though faded, blocks the luminescence, revealing the hidden images on the page.

© Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

[If the article is from the mag and not your own work, add this: This article was originally published in How It Works issue 126

For more science and technology articles, pick up the latest copy of How It Works from all good retailers or from our website now. If you have a tablet or smartphone, you can also download the digital version onto your iOS or Android device. To make sure you never miss an issue of How It Works magazine, subscribe today!