Gut feeling: Exploring the gut-brain axis

by Ailsa Harvey · 10/11/2019

How does the bacteria in your gut act like a 'second brain'?

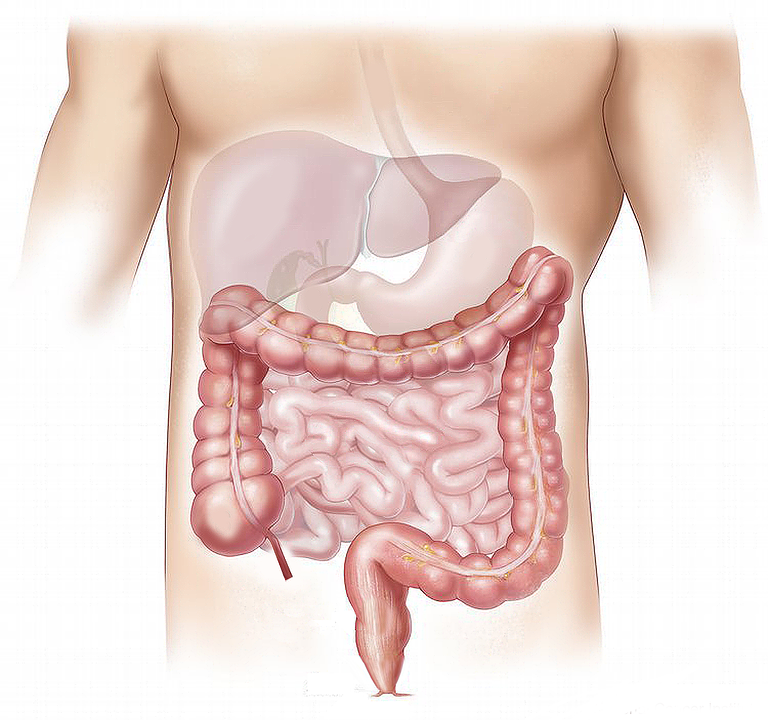

We all know that our mood and behaviour is controlled by the brain, but are we overlooking another important aspect of our neurobiology? There is an increasing amount of evidence to suggest that the activity of bacteria in your gut can significantly affect your brain. This relationship is called the gut-brain axis, and while its exact mechanisms and significance haven’t been fully figured out, it is thought that the microbes colonising your digestive tract are responsible for complex interactions between your digestive system and the nervous, endocrine and immune systems.

Your intestines are filled with bacteria. When you think of bacteria you probably think of the germs that make you sick, but we actually have a lot to thank these tiny microorganisms for. We rely on ‘good’ bacteria to help break down food, produce vital nutrients and defend us against harmful bacteria. But this could just be the tip of the iceberg. Scientists speculate that gut microbes can send signals to the brain via three different methods.

The first involves bacteria releasing neurotransmitters (chemicals that help to transmit nerve impulses) to trigger the neurons in your digestive tract, which in turn send signals to your brain via the vagus nerve. Some studies have shown that certain species of gut bacteria can produce serotonin, an important neurotransmitter that plays a role in regulating your appetite and mood.

A second proposed method is that microbes in the gut produce molecules called metabolites as by-products when they break down our food. These metabolites can stimulate an increase in the production of neurotransmitters by cells that line the gut (epithelial cells), which activate the vagus nerve. For example, a recent study found that some gut microbes can produce the fatty acids butyrate and tyramine, which promote the production of serotonin by certain cells.

The third hypothesis is that gut bacteria can influence the brain indirectly by triggering the immune system. Gut bacteria can stimulate immune cells to produce small proteins called cytokines, which travel through the bloodstream to the brain. It is thought that these proteins can influence the development and activity of microglia (the brain’s immune cells), which are responsible for removing damaged cells at an injury site. Researchers believe microglia also play a role in the regulation of appetite and metabolism.

Although there are few human studies at the moment, animal studies have linked the activity of gut bacteria to a variety of conditions, including Parkinson’s disease, obesity,

depression, anxiety, schizophrenia and cardiovascular disease, and they may also cause

certain types of strokes. While much more research will be needed to further investigate these initial findings, if links are confirmed it could revolutionise how we treat certain neurological disorders. Perhaps in the future doctors will be prescribing probiotic diets to supplement treatments.

This article was originally published in How It Works issue 106, written by Charlie Evans

For more science and technology articles, pick up the latest copy of How It Works from all good retailers or from our website now. If you have a tablet or smartphone, you can also download the digital version onto your iOS or Android device. To make sure you never miss an issue of How It Works magazine, subscribe today!