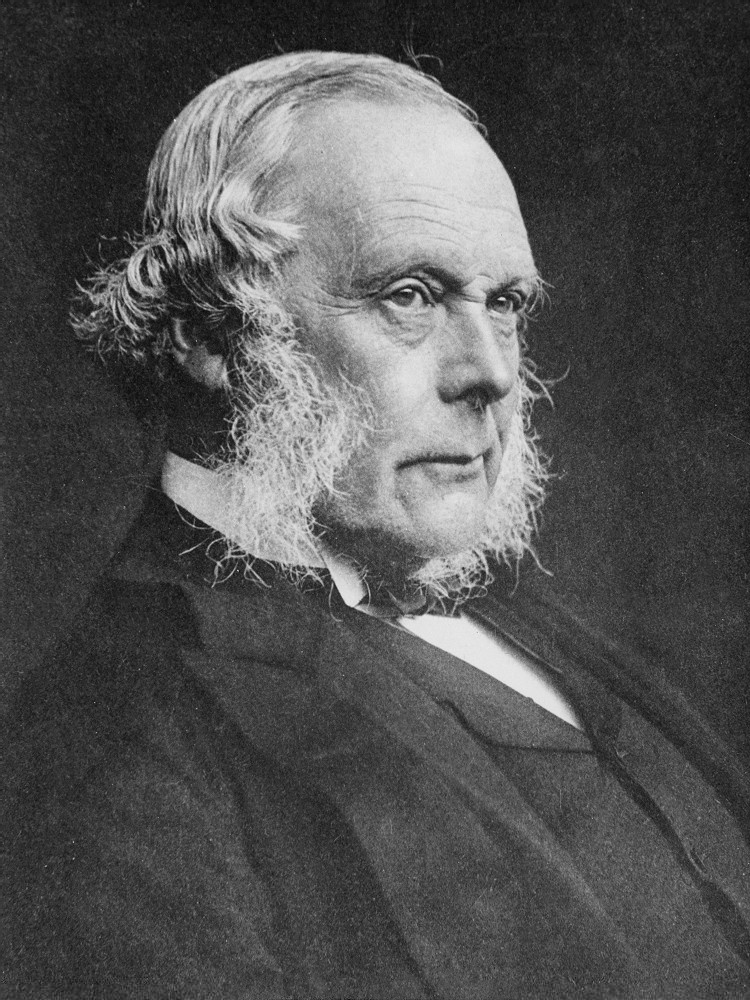

Heroes of Science: Joseph Lister

by Scott Dutfield · 16/12/2019

The man who used antiseptics to revolutionise surgery

Joseph Lister was born into a Quaker family on 5 April 1827. Having spent his childhood dissecting specimens and looking at tissue samples using his father’s microscope, the young Lister decided to become a surgeon. Despite his interest in comparative anatomy, he completed an arts degree at University College London (a secular alternative to Oxbridge). He eventually did go on to study medicine in 1848, graduating with several different honours and gold medals.

At this time surgery was developing as a speciality, with the introduction of proper training and the use of general anaesthetics. In December 1846, Lister witnessed the first use of ether anaesthetic in England. But, many patients still died after their operations from infection. People believed this was caused by poisonous air, or ‘miasma’. Surgeons often arrived in theatre straight from dissecting dead bodies and didn’t consider washing their hands between patients. They took pride in the ‘good old surgical stink’ of their unwashed operating gowns.

In 1853, Lister travelled to Edinburgh to learn from Professor James Syme, where he would transform the future of medicine. Three years later, Lister married Syme’s daughter Agnes, who would help him with much of his research.

By the age of 33 Lister had become professor of surgery at the University of Glasgow. He was a popular lecturer, known for making students laugh and investing his own money in a lecture theatre more suited to learning.

However, he was still frustrated by the high levels of infection on his wards. Other surgeons were using various antiseptics to treat infected wounds with limited success. Building on the work of Louis Pasteur, Lister’s revolutionary approach was to use diluted carbolic acid (now known as phenol) before infection set in.

He first tested it on patients with broken bones where the injuries were open to the air. He and his assistants washed their hands and instruments in carbolic acid before applying it to the site of the injury. Eight out of ten of his first patients fully recovered. Encouraged, he began using the system for operations.

When he published his first results in 1867 there was considerable opposition. He was seen by some as a dangerous charlatan, but Lister was undeterred. Gradually, his principles were adopted. In 1869, he left Glasgow to replace his father-in-law as professor of clinical surgery in Edinburgh. He would later develop a new method of fixing broken kneecaps with wire.

Towards the end of his life he was honoured with many awards, including a knighthood and elevation to the House of Lords as Lord Lister of Lyme Regis. He became Queen Victoria’s personal surgeon as well as one of her privy counsellors. He was also elected president of the Royal Society, following in the footsteps of Sir Isaac Newton. In the midst of this, he helped found what is now the Lister Institute of Preventive Medicine in Hertfordshire, UK.

The Big Idea: How Lister built on Louis Pasteur's work to revolutionise surgery

After reading Pasteur’s work, Lister became convinced that infection was caused by germs, not the surrounding ‘bad’ air. He soon began searching for an ideal antiseptic. He knew sewage plant engineers used carbolic acid to conquer the smell from rubbish and nearby fields irrigated with liquid waste. It was noted that the cows grazing there were no longer getting a disease known as ‘cattle fever’. Lister used these facts to develop a system where surgeons and assistants washed their hands and instruments and cleaned the wound with carbolic acid to prevent infection. This reduced the number of post-operative deaths from around 50 per cent to 15 per cent – a remarkable reduction at this time.

This article was originally published in How It Works issue 111, written by Sophie Beal

For more science and technology articles, pick up the latest copy of How It Works from all good retailers or from our website now. If you have a tablet or smartphone, you can also download the digital version onto your iOS or Android device. To make sure you never miss an issue of How It Works magazine, subscribe today!