How do coral reefs form?

by Scott Dutfield · 01/08/2020

Corals are team players, collaborating to build the largest living structures on Earth

Covering just 0.1 per cent of the world’s surface, coral reefs are home to around 25 per cent of all the species in the ocean. These seemingly static structures are constantly surrounded by colour and movement, and while they’re often mistaken for rocks or plants, the corals themselves are living animals; they belong to the group Cnidaria, along with jellyfish and sea anemones.

Corals can grow to vast sizes, but these aren’t enormous individual animals – they’re colonies made up of thousands of tiny creatures. On its own, each invertebrate is known as a coral polyp and can be as small as one centimetre in diameter. These polyps are sessile, meaning that they remain in a single spot once they’ve reached maturity and catch passing food with tentacles around their mouths.

The structure of a coral reef is provided mostly by the stony corals, or hard corals. These reef-building corals grow best in shallow tropical water with fast currents to bring food their way. Polyps slowly aggregate and connect their gastrovascular canals so they can share nutrients. Hard coral colonies gain their stony appearance through the secretion of calcium carbonate, a compound that forms a hard exoskeleton around the delicate polyps.

The hard skeletons and twisting shapes of reef corals provide shelter for a variety of creatures. Animals like shrimps and crabs defend homes made in the nooks between branches, and many species spawn around the reef to protect their young from the strong current. Single-celled algae called zooxanthellae even share the energy they produce from photosynthesis in exchange for lodgings within a polyp’s body.

The Great Barrier Reef

Comprised of over 2,500 individual reef systems and hundreds of tropical islands, Australia’s Great Barrier Reef is the most extensive reef ecosystem on the planet. It covers almost 350,000 square kilometres; it’s so large, in fact, that it can be seen from space.

It has incredible biodiversity. 1,500 species of fish, 4,000 species of mollusc and some 240 species of bird call the reef home. Anemones and sponges add colour, while crustaceans and marine worms fill the reef with movement. Threatened species like the green turtle and dugong can still be found here, and clouds of butterflies head to the islands for the winter.

The Great Barrier Reef is a haven for wildlife. Most of the ecosystem’s area has been a World Heritage Site since 1981, but its future is far from certain. Pollution, climate change, unsustainable fishing and coastal development all threaten this iconic reef.

This article was originally published in How It Works issue 127, written by Victoria Williams

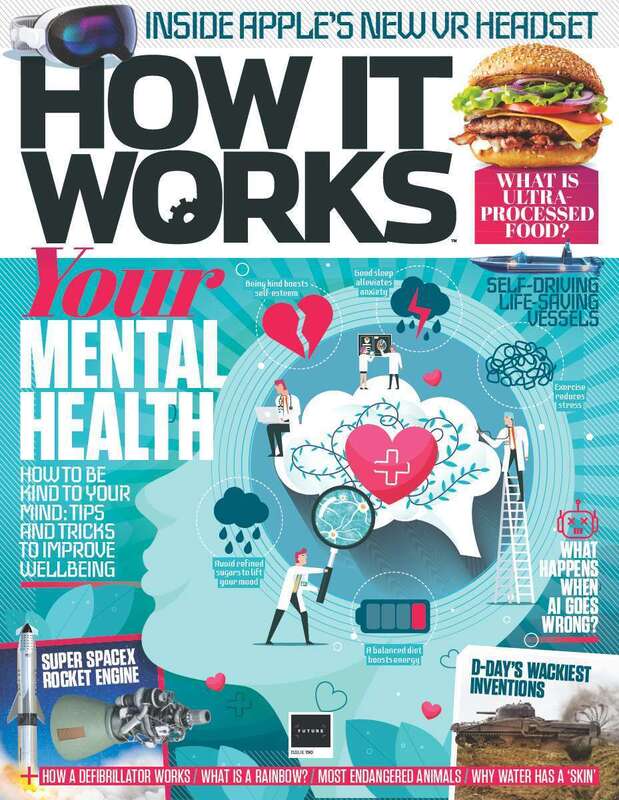

For more science and technology articles, pick up the latest copy of How It Works from all good retailers or from our website now. If you have a tablet or smartphone, you can also download the digital version onto your iOS or Android device. To make sure you never miss an issue of How It Works magazine, subscribe today!