How do ticks cause lyme disease?

by Scott Dutfield · 09/01/2020

The vampiric ectoparasite that can only survive by drinking blood

One of the most adaptive and resilient hitchhikers of the gruesome world of parasites is the hard-bodied tick. These hard-shelled masterminds rely on your blood because they lack sufficient energy to complete their lifecycle without indulging in a warm, crimson feast. They’re brought into the world as eggs unable to grow without latching onto a host, so they must find a small mammal or lizard in order for them to start developing.

The larva engorges itself on the fresh, warm blood of its first host before dropping to the ground exhausted and overindulged. They’re equipped with ferocious jaws yet unable to jump, so they can only lay in ambush when they need to feed again. They stretch out their clawed first pair of legs and then wait for an animal to pass, at which point they grab hold. When seeking their prey they wave their legs, looking for a signal that there is a host nearby.

You’re an easy target. She knows you’re there – the special sensory organs within her limbs can detect the carbon dioxide in your breath and the ammonia in your sweat. You’re getting closer, and suddenly she senses a spike in temperature, her cue to reach for opportunity and latch onto your skin with her tiny claws.

Beneath the protective plate guarding her soft body she is armed with a set of sword-like jaws. She settles somewhere after seeking out her favourite spots to lounge for a few days and punctures the skin with a miniscule, pointed tooth, allowing her saliva to ooze into the wound and keep your skin bleeding.

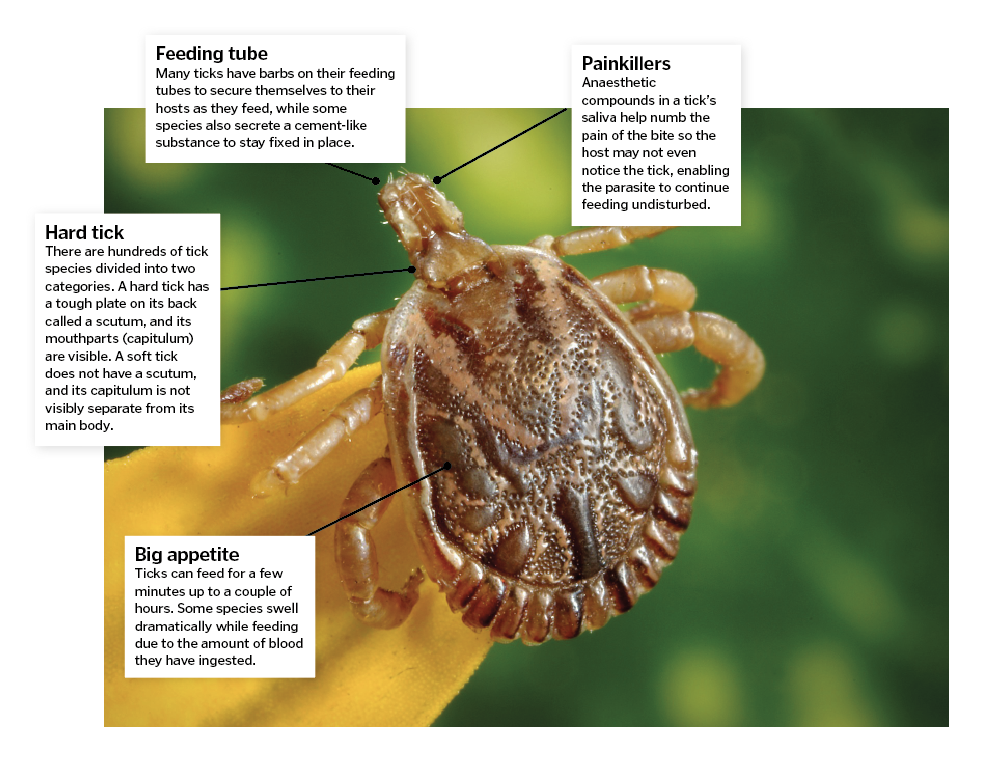

Tick anatomy

How these tiny parasites satisfy their bloodlust

Diseases transmitted by ticks

If you find that a tick is having a nibble on your skin, it is important to resist the urge to just pull it off. It’s embedded pretty deeply, and there is a risk of accidentally forcing the tick to vomit blood into your system. This could be riddled with disease. Ticks are known to transmit diseases including babesiosis and lyme. Instead of yanking this unwanted clinger-on off your skin, use thin tweezers to grab the tick as close to your skin as possible and gently pull it out, directly up from the skin. If you would like to check that the tick hasn’t exposed you to anything nasty, you can put it in a ziplock bag to have it checked by a medical professional if needed. If you do develop a rash or a fever in the weeks after removing a tick, go to the doctors as soon as possible.

[If the article is from the mag and not your own work, add this: This article was originally published in How It Works issue 109, written by Charlie Evans

For more science and technology articles, pick up the latest copy of How It Works from all good retailers or from our website now. If you have a tablet or smartphone, you can also download the digital version onto your iOS or Android device. To make sure you never miss an issue of How It Works magazine, subscribe today!