Meet the animals powered by the Sun

by Scott Dutfield · 22/06/2020

These creatures take inspiration from plant photosynthesis and use sunlight to feed themselves

As Earth’s natural solar panels, plants obtain energy from converting sunlight into food in a process called photosynthesis. It’s an ability that has ensured the survival of autotrophs – an organism that produces its own food – for around 2 billion years. But it turns out plants don’t hold the monopoly on photosynthesis, as a few animal species have also been found to dabble in the art of light conversion.

Take the pea aphid (Acyrthosiphon pisum), for example. Typically found feasting on the stems, leaves and flowers of alfalfa plants around the world, pea aphids have evolved

to mimic their leafy lunch. Rather than producing chlorophyll pigment for photosynthesis, these tiny insects can produce another pigment called carotenoids, which can also absorb sunlight and provide an energy boost for the aphids. Although this isn’t a complete replacement for the aphid’s plant-based diet, studies have shown green aphids produce significantly higher levels of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) – the body’s energy currency – than their white counterparts, who lack the carotenoid pigments. Pea aphids are a great example of how one species can mimic another to reap the same benefits through evolution.

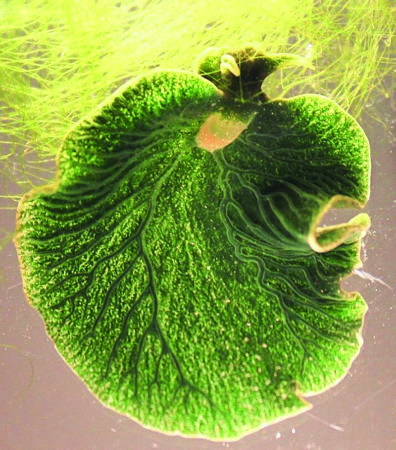

Just below the watery surface of salt marshes around the North American coastline, there is also a group of sun-worshipping slugs with a tendency to steal the ability to photosynthesise from their algae neighbours. Looking more like the leaf of a sycamore than a sea slug, sacoglossans are a group of marine invertebrates that feed on algae and in the process absorb their photosynthesis factories, chloroplasts. Known as kleptoplasty, sacoglossans can strip chloroplasts from their algal prey and relocate them into their own cells, where they continue to produce energy and sugars from sunlight. These sea slugs only need to feast on marine algae for the first two weeks of their life, which can sustain them for around 12 months.

One slug has taken this chloroplast kleptomania to the next level by stealing the algae’s genetic information to produce its own chloroplasts. Although sacoglossa slugs can survive for a whole year without eating before they run out of photosynthesis power, the emerald elysia (Elysia chlorotica) has evolved a way to make sure it never runs out of reserves. Initially grazing on algae and obtaining chloroplasts through kleptoplasty, the emerald elysia breaks into the nucleus of the algae and steals genetic information which codes for the production of chloroplasts in what’s known as a horizontal genetic transfer. This sea slug is then able to sustain itself on the energy produced through photosynthesis, even though they still chow down on an algal lunch from time to time.

With only a few examples of animals capable of exploiting photosynthesis, especially in vertebrate species, you’re not going to see green bears in the woods anytime soon. However, one vertebrate species has been discovered to harbour an algal hostage within its cells. It was previously believed that during the life cycle of the spotted salamander (Ambystoma maculatum), algae and a salamander embryo have a symbiotic relationship whereby both benefit from the other in the exchange of nutrients for oxygen. However, studies have shown that during development algae become incorporated into the salamander cells, where they live and provide energy to adult salamanders. It’s still relatively unclear as to how exactly the algae enter the salamander’s cells and why its immune system doesn’t deem the algae as a threat. But what is clear is that once inside, this microscopic mutualism is no longer beneficial to both sides. Trapped in the confines of an amphibian’s dark-pigmented body, access to a source of light is in short supply. Instead, these once-photosynthetic algae turn their hand to fermentation to produce food in the gut of the salamander.

This article was originally published in How It Works issue 134

For more science and technology articles, pick up the latest copy of How It Works from all good retailers or from our website now. If you have a tablet or smartphone, you can also download the digital version onto your iOS or Android device. To make sure you never miss an issue of How It Works magazine, subscribe today!