Prehistoric painting

by Ailsa Harvey · 10/10/2019

How ancient artworks provide a rare insight into the lives of Palaeolithic humans

Prehistoric cave paintings are believed to be among the first examples of human art. The remnants of images found in caves today provide archaeologists with a fascinating insight into the world of our Stone Age ancestors.

So how did they make the paint? Black paints could be made from a simple mixture of

charcoal and a binder, such as saliva or animal fat. The earliest coloured paints were made from naturally occurring minerals (known as pigments) such as iron oxides, which were ground into a powder before being mixed with a binder. These pigments were in high demand, and some prehistoric artists may have travelled 40 kilometres or more to gather them.

To make a typical cave painting, an outline was scored on the wall with a sharp stone, then marked out with charcoal. The image could then be filled in with a coloured pigment paint, and shaded to make it three-dimensional. The majority of cave paintings are illustrations of animals that roamed the land nearby, including lions, rhinos, bears and even sabre-toothed cats. Images of the humans themselves are much less common. One theory for this is that it was believed that the artwork was a link to a spirit world, and the depictions would increase luck when hunting. Campfires in the caves helped to give the impression that the painted creatures were alive, with the illustrations dancing on the walls. Outlines of human hands, also known as hand stencils, are a common sight among cave paintings, thought to be a sort of artist’s signature.

Scientists can estimate when a cave painting was made using radiometric dating, either using the rate of decay of the isotope carbon-14 in the pigments, or the rate of uranium decay in the surrounding rocks. Some paintings in Europe are thought to date back as far back as the Upper Paleolithic period, making them up to 40,000 years old. The European examples are perhaps the most well-known, but prehistoric cave art have been also been found in Africa, Asia and Australia, with (relatively) more recent examples in the Americas dating back nearly 10,000 years.

Based on the discoveries so far, cave art seems to have become less popular as warmer climates allowed humans to begin settling outside of caves. Discoveries of prehistoric art continue to fascinate us today and provide a unique insight into the culture of our distant ancestors.

The prehistoric palette

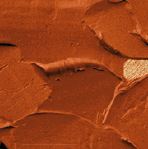

Ochre

Ochre pigments can come in shades ranging from red to yellow to brown depending on its mineral blend, but they all contain iron oxide. Its texture allows it to be easily mixed with other pigments.

Carbon black

Monochrome paintings were a simple mix of carbon black and a binder. The colour was made from burning wood or plants, which created charcoal. It was often used as a ground layer for a polychrome image.

Kaolin

Kaolin is a whitecoloured clay and one of the Earth’s most abundant minerals. Its name originates from the town of Gaoling in China, which is renowned for having rich kaolin deposits.

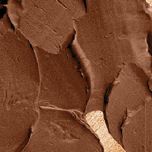

Umber

Umber is another combination of iron and manganese that is darker than both sienna and ochre. The shade of its reddish-brown colour is dependent on which mineral was dominant in the mix. It could be heated to the even darker colour of burnt umber.

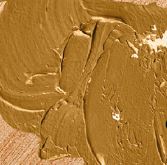

Sienna

A mixture of iron oxide and manganese oxide, raw sienna is a pigment with a yellow-brown colour. When heated, it turned into burnt sienna, which is darker in tone and redder in colour.

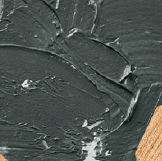

Manganese oxides

One of the darkest colours used, manganese oxide could create shades that were brown, grey or black. Manganese deposits weren’t common in caves adorned with artwork, so it’s assumed painters would trek long distances to find a source.

This article was originally published in How It Works issue 98, written by Jack Griffiths

For more science and technology articles, pick up the latest copy of How It Works from all good retailers or from our website now. If you have a tablet or smartphone, you can also download the digital version onto your iOS or Android device. To make sure you never miss an issue of How It Works magazine,

More

- Next story F-35: How to build a fighter jet

- Previous story Animal astronauts