Race to the Poles

by Scott Dutfield · 13/09/2020

How pioneering explorers battled extreme conditions to reach the ends of the Earth

By the turn of the 20th century few places on Earth remained uncharted. Since the Age of Discovery humans had developed the means to cross oceans and explore continents in the interest of developing trade routes and expanding empires. The frozen expanses of the poles presented extreme challenges but offered different incentives: the irresistible lure of the unknown and the glory of getting there first.

Peary versus Cook

The geographical North Pole lies at the latitude of +90° on a thick shelf of sea ice. The frozen sea shifts with the seasons, making journeys across the Arctic particularly treacherous. Explorers also face temperatures that can drop to -50 degrees Celsius, wind speeds of up to 90 kilometres per hour and the prospect of being hunted by polar bears. After several failed expeditions in the 1800s, in 1909 two successful missions to the North Pole by American explorers were, curiously, reported within a week of each other.

The first was Dr Frederick Cook who, accompanied by native hunters from Greenland, claimed to have reached the pole on 21 April 1908. The team left from Annoatok, Greenland, in February 1908 and travelled an average of 24 kilometres per day using dog sleds, plus a collapsible boat to cross the water where necessary. According to Cook’s memoirs he used a sextant to determine his latitude and calculated his position as “a spot which was as near as possible” to the North Pole. However, a perilous return journey over the fractured, drifting ice delayed their return to civilisation and meant they were unable to send word home for another 14 months.

In August 1908, while Cook was missing, presumed dead, his former colleague US Navy Commander Robert Peary set off on what was his ninth Arctic expedition. Using the so-called ‘Peary system’, his 50-man party rode dog sleds to perform a relay to drop supplies ahead along the route. Unlike Cook, Peary’s team did not take boats, so when the ice fractured they were sometimes left stranded for days until the gaps closed up again. When they were moving they covered an average of 21 kilometres per day. Peary took regular sextant measurements to make sure they were still heading north. On 6 April 1909 he recorded a latitude of just over +89° and wrote in his journal, “The Pole at last! […] my dream and ambition for 23 years. Mine at last.”

The announcements of their respective successes almost coincided due to Cook’s homeward delays and Peary’s remarkably fast return trip. Cook’s story was reported on 2 September 1909, while Peary’s was published on 7 September, but their achievements were overshadowed by the bitter feud that followed. Almost immediately Peary and his expedition benefactors dismissed Cook’s attempt. Peary even took the matter to Congress in order to get the government to officially recognise his achievements instead of Cook’s claims.

To this day there are doubts regarding both Cook and Peary’s claims; the explorers’ accounts and any remaining evidence from both expeditions have been reexamined many times. Questions have been raised about the accuracy of both men’s latitude measurements, reported travel speeds and unusual omissions from their journals. It’s unlikely that there will ever be a definitive answer as to how close each man truly came to the North Pole, and who – if either of them indeed did – reached it first.

Amundsen versus Scott

Less than two years after Cook and Peary’s feats first made headlines, preparations for another head-to-head polar race were just getting underway on the other side of the world. In January 1911 two teams of explorers arrived at the Antarctic determined to be the first to reach the South Pole.

The geographical South Pole is located at the latitude of -90° on one of the most inhospitable places on the planet. Antarctica is the coldest place on Earth, holding the record for the lowest observed temperature (at ground level) of -89.2 degrees Celsius. The majority of the inner ice shelf is between two and four kilometres thick, so explorers may experience altitude sickness as they attempt to cross the continent. Antarctica is also home to some of the world’s strongest winds; certain areas can experience gusts of over 198 kilometres per hour. What’s more, the continent is surrounded by the roughest and stormiest waters on the planet – the Southern Ocean – so both teams faced significant dangers before their expeditions even began.

The competing expeditions were led by Norwegian Captain Roald Amundsen and British Captain Robert Falcon Scott, both of whom were already renowned explorers. Scott had previously tackled the Antarctic during the 1901–1904 Discovery Expedition with fellow explorers Ernest Shackleton and Dr Edward Wilson, making it to -82° latitude – closer to the pole than anyone had reached before. Scott had been granted £20,000 funding from the government for the new expedition, and his preparations were given a lot of media attention.

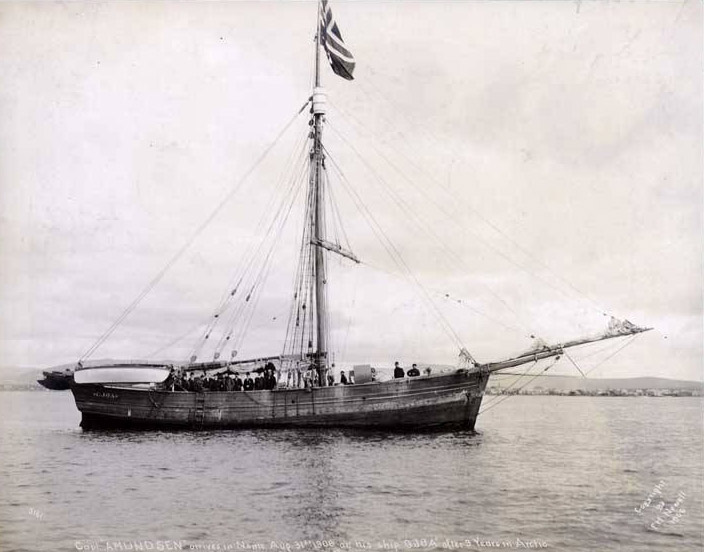

While Scott’s expedition intentions were public, Amundsen kept his own polar plans secret. He was already organising an Arctic expedition when Peary and Cook’s claims shattered his lifelong dream of being first to the North Pole. Rather than abandoning the expedition altogether, he revised the plans to make an attempt to the South Pole instead. Even Amundsen’s own crew were still under the impression they were heading to the Arctic until he revealed the truth en route.

Scott’s team arrived in Antarctica on 4 January 1911 at Cape Evans. While they were setting up base camp and preparing for the trek ahead they were completely unaware that Amundsen’s crew had landed just 640 kilometres away in the Bay of Whales on 14 January. Both teams spent most of the year making preparations for the expeditions, laying supply drops along their respective routes before setting off in the Antarctic spring – Amundsen on 20 October and Scott on 1 November.

Key differences between the tactics and equipment of the two crews spelled success for one and tragedy for the other. Amundsen’s small, specialised team included champion skiers and expert dog handlers. They had specially modified skis, wolfskin furs, windproof suits and knew to wear their layers loosely to avoid sweating so much – a tip Amundsen had learned from the Inuits during a previous Arctic expedition. They reached the South Pole on 14 December and returned safely to base camp on 25 January 1912.

Scott’s team was less experienced with both the cold weather and skiing. They brought ponies and motor sleds, but this soon proved to be a grave mistake. Both were unable to cope with the extremes of Antarctica; the sleds failed and were abandoned, and the weakened ponies were eventually shot for food. They reached the pole on 17 January 1912, devastated to find the Norwegian flag already firmly planted there.

Scott’s team were suffering from malnutrition, starvation, frostbite and hypothermia as the temperatures dropped to around -30 and -40 degrees Celsius. None of them survived the return to base camp. Scott ran out of rations and fuel and was trapped in his tent by a blizzard, despite being just a few miles away from a supply stash. His tragic last journal entry on 19 March read, “We shall stick it out to the end, but we are getting weaker, of course, and the end cannot be far. It seems a pity, but I do not think I can write more.”

Amundsen sent word of his historic success on 7 March 1912 and was duly hailed a hero. However, his glory was later eclipsed when the world learned of the fate of Scott and his men, who were seen as martyrs.

As with Peary and Cook, Amundsen and Scott’s journeys have been reexamined over the years – not to dispute whether or not they reached the South Pole, but to determine the combination of factors that led to Scott’s failure.

The end of an era

These pioneering expeditions of the early 20th century were among the last of what became known as the ‘heroic’ age of polar exploration. These men were admired for the sheer determination it took to face such harsh conditions with limited resources, pushing their physical and mental strength to the absolute limit in the pursuit of immortality.

This courageous era of discovery drew to a close after World War One, when engineering and technological advancements made such journeys – relatively speaking – much more straightforward to complete.

This article was originally published in How It Works issue 122, written by Jackie Snowden

For more science and technology articles, pick up the latest copy of How It Works from all good retailers or from our website now. If you have a tablet or smartphone, you can also download the digital version onto your iOS or Android device. To make sure you never miss an issue of How It Works magazine, subscribe today!