The History of Christmas

by Scott Dutfield · 25/12/2020

From Ancient Egyptian festivals to current celebrations, how has history shaped Christmas around the globe?

For many people, Christmas is the most magical time of the year. While modern Christmas traditions seem extremely commercial, aspects can be traced back to ancient roots. A huge variety of cultural customs have merged together in modern times, with the rise of the internet and travel enabling diverse celebrations to be shared and adopted. Singing, decorating and eating specific meals can be observed in many areas of the globe. But each country still holds onto their ancestors’ festive ways to keep traditions alive.

Lighting up the coldest and gloomiest months of the year has been a common theme across thousands of years of civilisation. How has history forged the Christmas of today? Here’s how Christmas has become a time where we indulge in festive foods, drag pine-shedding trees into our homes, light up the streets and send little cards to the people we know.

Ancient Egyptian festivals-1520 BCE.

Ancient Egyptians celebrate the birth of Horus, the son of the gods Isis and Osiris, during a festival on 25 December. This is the first record of this date being celebrated. Festivities involve large banquets, the burning of lamps and decorating homes with green palm leaves.

Roman Saturnalia-497 BCE.

In early winter the Romans celebrate the Saturnalia festival, honouring Saturn, the god of agriculture. Feasts take place, and livestock is slaughtered before the winter and eaten. These celebrations continue from the end of December through to the beginning of January. (Image credit: Marco Massimo/ Pixabay)

Celebrating the 25th-336 CE.

This is the earliest official record of 25 December being a celebration of Jesus’s birth. For the first three centuries of the millennium his birthday isn’t celebrated, and Easter is seen as the holier day by the early Christians. (Image credit: eliza28diamonds/Pixabay)

Viking Yule – 800 CE.

The Vikings celebrate a period of 12 days, beginning on 21 December. Referred to as ‘Yule’, this period involves drinking, feasting, banquets, games, song and a sacrifice to the gods. The evergreen tree, which we now also know as the Christmas tree, is used as a symbol of life for the Vikings, who decorate them with gifts and carvings to encourage the spirits of all plants to return in the spring.

The fear of Odin – 934

King of the Norse gods, Odin flies over towns during Yule to decide who will prosper and who will perish. King Haakon I brings Christianity to Norway, aligning old pagan beliefs with the dates of Christian festivals.

Medieval fasting-1038

During this time there are the first mentions of people fasting until Christmas Eve. Fasting before Christmas provides a good excuse for a large-scale feast when Christmas finally comes around.

Presents for peasants-Middle Ages

On Boxing Day, the poor go to the houses of the rich and ask for food and drink. During Christmas time it becomes an opportunity for the upper class to repay society by providing for the less fortunate. Christmas Day isn’t as pleasant as it may sound for the less wealthy, as the day often coincides with ‘quarter day’ – one of four days of the year when rent is due, and poorer tenants struggle to pay.

Early Christmas markets-1298

Vienna’s Christmas markets in the Middle Ages display similar scenes to the Christmas markets seen around Europe and elsewhere today. In these early markets, citizens are given permission to hold the stalls during Advent, in the run-up to Christmas Day.

Tudor pies-1500s

On the 12th night of Christmas, Tudor households bake a fruitcake to be shared with guests. This isn’t just a dessert, but an opportunity to become ‘king’ or ‘queen’ for the rest of the night’s celebrations. A coin or dried bean is hidden inside the cake, and whoever receives it wins the title.

Introducing Japan to Christmas-1549

St Francis Xavier arrives in Japan in 1549 and attempts to bring Christianity to the country. A few years later the first Christmas celebrations take place in there. In modern times, festive decorations line most streets in Japan at Christmas time.

Elizabethan Christmas-1550-1600s

An important part of an Elizabethan Christmas is the food. It is an opportunity to demonstrate a family’s wealth to numerous guests and friends. Roasted peacock and swan are the ultimate birds of choice in these extravagant Christmas feasts. Poorer members of the community are often invited.

Cancelling Christmas-1644

The English Parliament bans all Christmas celebrations. The puritans believe that some of the celebrations taking place – such as excessive drinking and eating – are unnecessary and don’t reflect the true meaning of Christmas. Under Oliver Cromwell’s reign, Christmas involves only fasting and prayer.

America loses Christmas-1659-1681

The puritan ban on Christmas celebrations and festivities soon spreads to the English colonies in America. Showing any sort of Christmas spirit in Boston comes with a hefty penalty of five shillings (the equivalent of around a £25 fine today).

Christmas returns to Britain-1660

Following the death of Oliver Cromwell, Charles II is restored to the throne. This news is joyfully received by the public as it means the return of Christmas and the freedom to celebrate once again, as the strict puritan laws are overturned.

A new New Year-1752

Most of us are used to celebrating the end of the Christmas season on New Year’s Day on 1 January. Before 1752, however, New Year’s Day was celebrated on 25 March. As a result 1751 is a short year in the calendar, only running from 25 March to 31 December as the start of the new year changes to 1 January.

12th night parties-1700-1800s

After the revival of Christmas in England, parties are back in full swing. The 12th night (5 January) had been celebrated since the Middle Ages, but the games, food and drink become even more popular with people during this time period.

Twas the night before Christmas-1822

Clement Moore writes A Visit From St Nicholas, more often known as Twas The Night Before Christmas. This poem has remained popular, starting an annual tradition for many families to read it on Christmas Eve.

The first Christmas cards-1843

The Victorians start the tradition of sending Christmas cards. The first-ever is believed to have been designed and printed in England by John Callcott Horsley. In 1846, 1,000 cards with the first card’s design are sold for a shilling each.

Creating the cracker-1847

Confectioner Tom Smith invents the Christmas cracker, inspired by a French sweet wrapped in paper twisted at both ends. With the aim of beating his competitors in sales, he also adds a motto inside, then replaces the sweet with a gift. In 1860 the ‘bang’ is added.

More presents-Early 1900s

The start of the 20th century sees an increase in gift-giving, as manufacturers and shops begin to fully explore the commercial possibilities of the festive season, encouraging people to buy presents for each other as a symbol of the Christmas spirit.

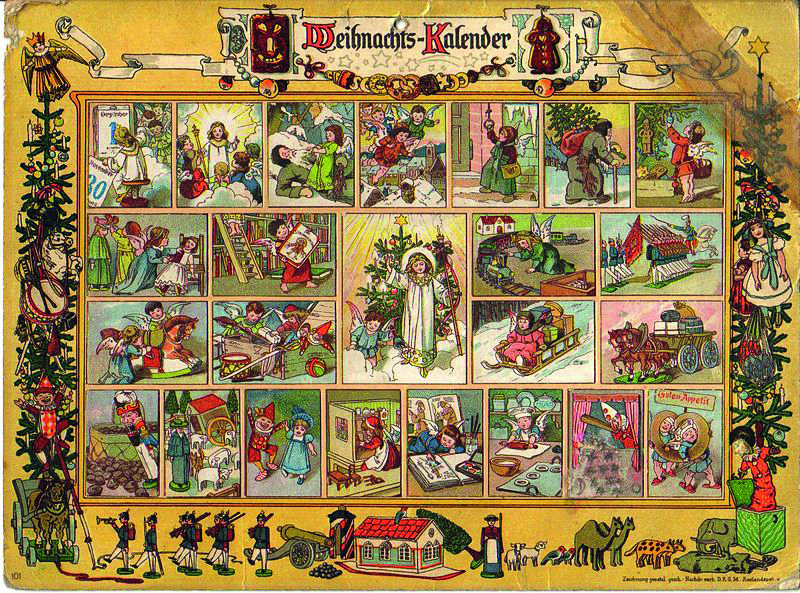

Advent calendars-1904

The idea of today’s advent calendars comes from a German man named Gerhard Lang. He takes inspiration from his mother, who would count down to Christmas with him as a child by giving him baked meringue treats to soothe his impatience. As an adult, Lang works to improve his design, resulting in the chocolate calendars that are still popular today.

Christmas truce-1914

In World War I, enemy forces put aside their differences for one night only, to demonstrate the influence of the Christmas spirit. When British soldiers hear the German opposition singing Christmas carols in their trenches during the Christmas of 1914, the two sides stop fighting and meet in no-man’s land to

exchange gifts and play games together.

Christmas Blitz-1940

After London had been bombed for 57 consecutive nights by German aircraft and with Christmas Day drawing closer, many people in the city spend Christmas Eve in the less homely setting of an air raid shelter. Many continue to celebrate Christmas from there.

This article was originally published in How It Works issue 132, written by Ailsa Harvey

For more science and technology articles, pick up the latest copy of How It Works from all good retailers or from our website now. If you have a tablet or smartphone, you can also download the digital version onto your iOS or Android device. To make sure you never miss an issue of How It Works magazine, subscribe today!