The Human Body: What is a mouth ulcer?

by Scott Dutfield · 08/11/2019

Image credit: Scientific Animations

How these common but painful sores form and develop

They’re the mouth irritations that can make eating a meal unbearable, but the cause of mouth ulcers or canker sores is still relatively unknown. At least 20 per cent of the population is affected by mouth ulcers, and they vary in severity – these sores can appear as minor ulcers normally lesss than five millimetres, while major ulcers can stretch one centimetre in diameter. You can also have several ulcers clustered together to form large irregular ones known as Herpetiform ulcers.

There are two ways they can form and many occur as a result of trauma, such as biting your lip or cheek, or burning your mouth. However, the second form, known as recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS), has been linked with a whole host of conditions. Recurring sores can be due to bacterial infections, immune disorders, stress and smoking. Genetics also plays a large role in the likelihood of their repeated occurrence. Around 40 per cent of sufferers have a family history of experiencing ulcers, and this is thought to be linked with the increase of a particular antigen that the body produces, potentially causing the RAS.

Ulcers typically heal after a few weeks, though those who suffer with RAS may experience them repeatedly. An ulcer lasting more than a few weeks could be linked with oral carcinoma, a form of mouth cancer.

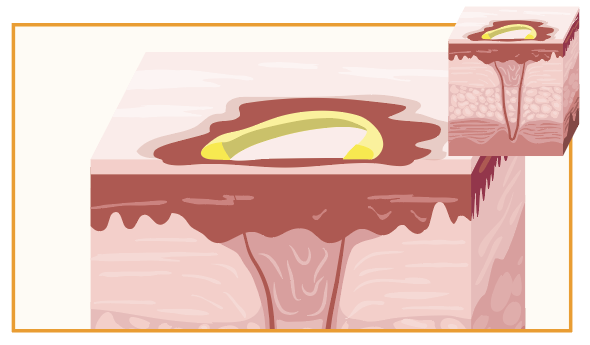

Formation of a canker sore

Most types of mouth ulcer usually have a relatively short life

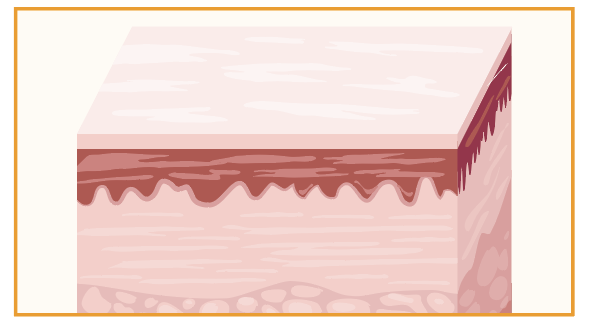

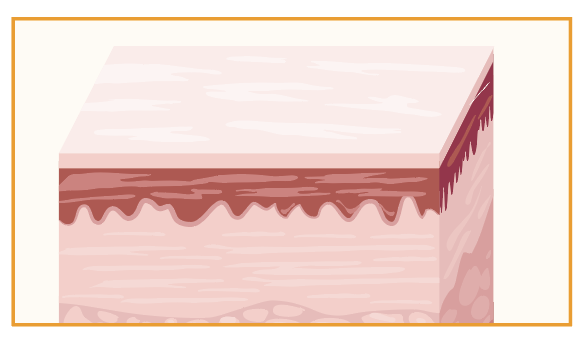

Healthy tissue

The healthy oral skin is comprised of several layers, known as the oral mucosa, which is the first physical defence against damage.

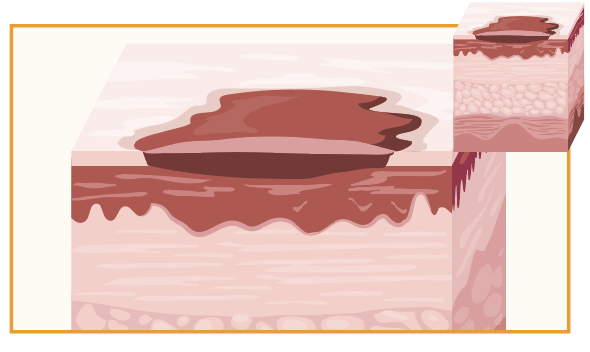

Trauma

Once the mucosa has been damaged, inflammation occurs at the trauma site, determining the ulcer’s size.

Cell death

Cells within the mucosa’s layers will break down, creating the crater for the ulcer to fill.

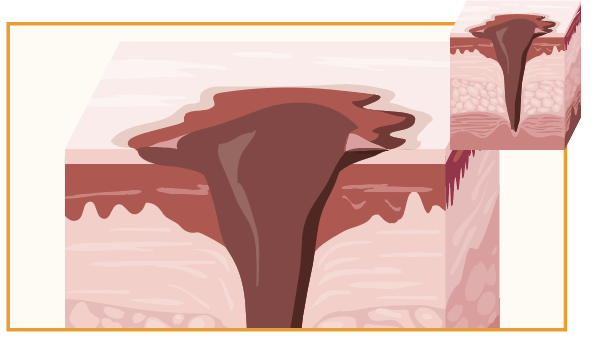

Ulceration

A cocktail of blood, tissue and bacteria fill the cavity, while a protein needed for healing wounds, fibrin, fills a membrane, giving the ulcer its typical white-yellow appearance.

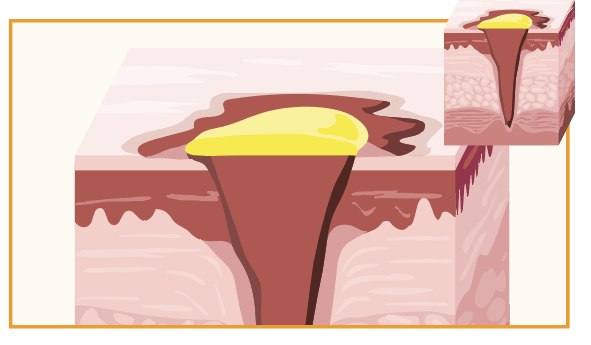

Breakdown

Once healthy tissue has been replaced within the ulcer’s cavity, the fibrin membrane breaks down.

Healed

The oral mucous is now back to its original healthy state.

Illustrations by Ed Crooks

This article was originally published in How It Works issue 123

For more science and technology articles, pick up the latest copy of How It Works from all good retailers or from our website now. If you have a tablet or smartphone, you can also download the digital version onto your iOS or Android device. To make sure you never miss an issue of How It Works magazine, subscribe today!