Who was Robert Hooke?

by Ailsa Harvey · 23/04/2021

Meet the English polymath who discovered the building blocks of all life

Not confining himself to one field, this 17th-century scientist was responsible for contributing to our knowledge of everything from mathematics and mechanics to biology and astronomy. Born on the Isle of Wight, off the south coast of England, Hooke began his series of interests as a keen artist.

He lived with his parents until the age of 13, and due to being a sickly child was a latecomer to education. Instead of attending school, he spent much of his childhood drawing from his bedroom. But his lack of an early education didn’t stop Hooke realising his genius. It was his later enrolment at Westminster School in London that would take him down a scientific path. Here he discovered that his talents lay beyond painting, particularly in mathematics, mechanics and languages.

Many people are aware of Hooke’s work in microscopy, but in 1653, at the age of 18, Hooke attended Christ Church College at Oxford, where he spent much of his time building telescopes. Shortly after in 1660, he discovered a physical law that would later be named after him: Hooke’s law. It states that the force needed to extend or compress a spring is proportional to the distance it is stretched.

In 1662, two years after the Royal Society was founded, Robert Hooke was named a curator of the society. Today this is the oldest independent scientific academy, and Hooke’s broad scientific interests helped set the society in motion during its early years. During his time with the society he carried out experiments and made further discoveries alongside its other members. In 1663 his interests in meteorology and seafaring saw him contribute to the invention or improvement of the five main meteorological instruments: the barometer, thermometer, hydroscope, rain gauge and wind gauge.

“By the means of telescopes, there is nothing so far distant but may be represented to our view, and by the the help of microscopes, there is nothing so small as to escape our enquiry"

Hooke is certainly best known for discovering and observing the living cell, but this came with multiple lesser known findings along his journey in microscopy. As he researched down to the extent of what the available microscopes could see, he discovered spores in mould, he became the first to examine different fossil types with a microscope and he uncovered how mosquitoes and lice suck blood.

To further his areas of expertise, following the disastrous Great Fire of London in 1666, Hooke was given the opportunity to try his hand at architecture. Alongside Sir Christopher Wren, he designed a monument to commemorate the fire. With the lead architects both being scientists, they decided to add some practicality to the aesthetic. Underneath this 60-metre-tall structure, Hooke built an underground laboratory where he could conduct many of his science experiments, while the central passage was built to house a large telescope.

There are few areas of science which Hooke didn’t venture into. Since his death in 1703, scientists continue to be inspired by and benefit from Hooke’s findings as they delve further into the microscopic world he opened up. As he quotes in his book Micrographia: “By the means of telescopes, there is nothing so far distant but may be represented to our view, and by the the help of microscopes, there is nothing so small as to escape our enquiry”.

Cells' first witness

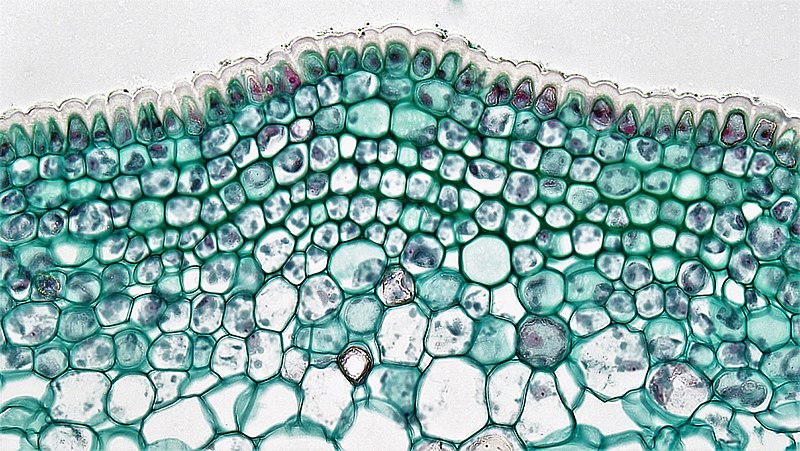

Every living thing is made up of cells, and the study of these structures enables biologists to understand how all organisms live, as well as develop new medical science. Before 1665, however, these cells had never been seen. With a keen drive to explore what lay beyond the visible world, Hooke reinvented his compound microscope to allow him to observe finer details.

Using three lenses and a stage light, he was able to increase the size of what he was viewing, with the light adding even more clarity. As he placed a piece of cork underneath his improved microscope, he was presented with its hidden structure. The cork looked like it was covered in pores, with packed shapes that reminded Hooke of the small cell rooms in a monastery. It was then that he named these structures ‘cells’.

For more science and technology articles, pick up the latest copy of How It Works from all good retailers or from our website now. If you have a tablet or smartphone, you can also download the digital version onto your iOS or Android device. To make sure you never miss an issue of How It Works magazine, subscribe today!