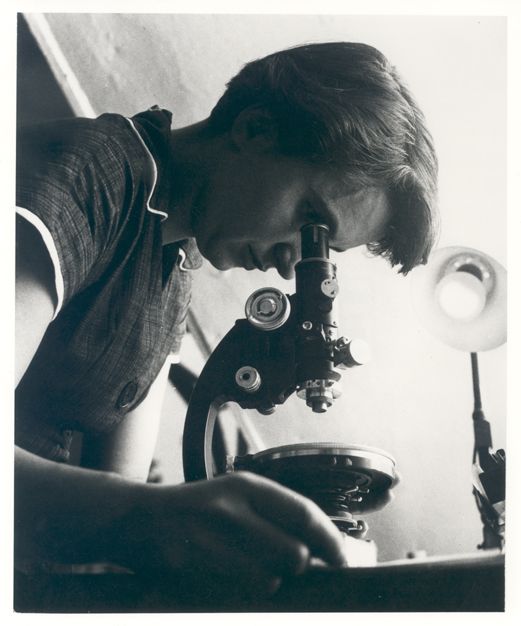

Heroes of science: Rosalind Franklin

How the work of the ‘Dark Lady of Science’ helped to solve the mystery of DNA

Rosalind Franklin was not the most popular figure in science. Nicknamed the ‘Dark Lady’ by her male colleagues for being hostile and troublesome, it’s hard to say if this really described her nature or if it was a result of patriarchal prejudice. What is certain, however, is that she lived in the darkness of these men’s shadows.

Rosalind’s photographs of DNA fibres helped to establish its double helix structure

Born in London in 1920, Rosalind attended St Paul’s Girls’ School – one of the few institutions in the country at the time that taught chemistry and physics to girls. She excelled in these subjects and by the age of 15, she knew she wanted to become a scientist. Her father tried to discourage her, as he knew that the industry did not make things easy for women. But Rosalind was stubborn. In 1938, she was accepted into Cambridge University where she would study chemistry.

On graduating, Rosalind took up a job at the British Coal Utilisation Research Association. By this point the Second World War was in full swing, and Rosalind was determined to do something to help the war effort. Her research into the physical structure of coal was pivotal in developing gas masks that were issued to British soldiers, and it won her a PhD in physical chemistry as well.

In 1946, Rosalind moved to Paris to work as a researcher for Jacques Mering – a crystallographer who used X-ray diffraction to work out the arrangement of atoms in substances. Here she learnt many of the techniques that would aid her later discoveries.

Five years on, she was offered the role of research associate in King’s College London’s biophysics unit. Rosalind arrived while Maurice Wilkins, another senior scientist, was away. On his return, he made the assumption that this woman had been hired as his assistant. It was a bad start to what would become a very rocky relationship.

Despite the tense environment in the lab, Rosalind rose above and beyond the task, working alongside PhD student Raymond Gosling to produce high-resolution photographs of crystalline DNA fibres. The structure of DNA was a puzzle that Maurice and two of his friends – Francis Crick and James Watson – had been trying to piece together for years. But with a single photograph, simply labelled ‘Photo 51’, Rosalind and Raymond had cracked it.

One photograph, called Photo 51, showed two clear strands. This indicated a double-helical structure.

Without her permission, Maurice took this photograph and showed it to Watson and Crick. It was the final piece in their puzzle – DNA was indeed a double helix. The trio published their findings, and in 1962 they were awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine.

By a tragic twist of fate, Rosalind died of ovarian cancer four years previous to that. The doctors at the hospital she was treated at believed that prolonged exposure to X-rays was a possible cause of the disease. She had made the ultimate sacrifice for the sake of science, with no living reward.

The big idea – DNA

Rosalind used X-ray diffraction to analyse the physical structure of substances. This involves firing X-rays at them. When the X-ray hits the substance, the beam scatters, or ‘diffracts.’ Rosalind recorded the pattern created by this diffraction in order to discover how the material’s atoms were arranged. The molecular structure of DNA had been puzzling scientists for years. Rosalind found that by wetting DNA fibres, the resulting images were a lot clearer. One photograph, called Photo 51, showed two clear strands. This indicated a double-helical structure, explaining how cells pass on genetic information.

Five facts about Rosalind Franklin

Faking a death

Even during her experiments, Rosalind was unconvinced that DNA was helix-shaped, and even once sent her colleagues a notice commemorating the ‘death’ of helical DNA.

Beyond DNA

In addition to her work with DNA molecules, Rosalind also carried out pioneering research into the tobacco mosaic and polio viruses.

Girl power gone sour

Sexism was rife at King’s College, where even Rosalind was accused of discriminating against women. In a letter to her parents, she allegedly referred to one lecturer as “very good, though female.”

Not giving up

Rosalind tirelessly continued to work throughout her cancer treatment and was even given a promotion during the process.

No Nobel

Many people argue that the Nobel Prize should also have been awarded to Rosalind. But when the list of nominees was released 50 years later, it was revealed that, remarkably enough, she hadn’t even been nominated.

For more science and technology articles, pick up the latest copy of How It Works from all good retailers or from our website now. If you have a tablet or smartphone, you can also download the digital version onto your iOS or Android device. To make sure you never miss an issue of How It Works magazine, subscribe today!