How did the slave trade end?

by Ailsa Harvey · 27/05/2021

Why the British Empire stopped these harrowing transatlantic shipments and their human cargo

Beginning in the 1500s, the slave trade saw millions abducted from their homes and shipped against their will to endure a life of manual labour and mistreatment. Mainly targeting Africa, people were transported across the Atlantic to America, where they would be auctioned.

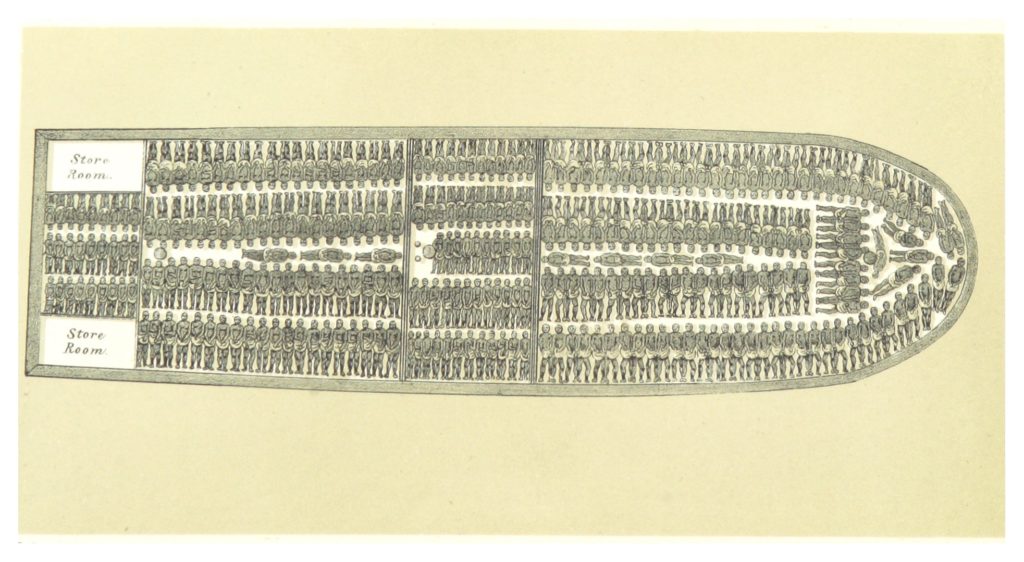

Having been split from their families, people were forced aboard cramped and disease-ridden ships for months. Life at sea involved brutal physical and emotional abuse, with around 15 per cent dying on the journey. Some feared losing their lives on board, while others feared the lives they were sailing towards, and were force fed by crew as they tried to starve themselves. Objectified and sold in a foreign land in exchange for goods such as cotton, sugar, tobacco and ginger, how could such an unjust and profit-driven operation continue for centuries? And how was this entrenched and barbaric system eventually banned?

When Britain explored other countries, encountering diverse and unfamiliar civilisations, instead of embracing these new cultures, Britons were much more interested in the available land and the people they could utilise for economic gain. The attitudes to race at the time meant that the government allowed this unjust treatment of innocent people. Because the slave trade was legal, those who protested against it needed to find a way to reach those in power to bring about change. It took a combination of enslaved activists and distant onlookers to battle to bring these centuries of torment to a close. As slaves spoke out about their own experiences and those in parliament began to acknowledge the barbarous practices involved, the laws on the trading of people were revisited.

When slavery was first abolished, no more slave ships were allowed to set sail. But this didn’t include freeing those who were already held as slaves. It wasn’t until 1838 that all slaves in the British Empire were granted freedom. None of them were given any form of compensation for a lifetime of anguish and torture, while owners were paid by the government for the loss of each slave.

The anti-slavery movement

Throughout Britain’s involvement in the slave trade, there were always those who acknowledged the injustice that came with forcefully transporting, owning and selling other human beings. As slavery became more prevalent, more people let their disapproval be known.

Two of the most influential abolitionists were Thomas Clarkson and William Wilberforce. People had heard some stories of the conditions faced by slaves, but Clarkson spent time creating an in-depth study of the trade. Publishing his findings on how slaves were being treated worse than animals, he spread this vital knowledge. Travelling across Europe, he campaigned against these wrongdoings, creating a mass movement by recruiting supporters.

William Wilberforce played his part from inside parliament. Inspired by the work of Clarkson, he spent 18 years introducing anti-slavery motions in parliament. After much persistence, and many persuasive speeches, his case was won and the law was changed.

For more science and technology articles, pick up the latest copy of How It Works from all good retailers or from our website now. If you have a tablet or smartphone, you can also download the digital version onto your iOS or Android device. To make sure you never miss an issue of How It Works magazine, subscribe today!