How Did People Translate Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs?

The last known hieroglyphic inscription from ancient Egyptian times in the Temple of Philae in southern Egypt. It was written approximately 1600 years ago. Shortly after, this written language was lost to history forever and only lived on as the spoken language Coptic. So how did we manage to decode the mysterious inscriptions hundreds and hundreds of years after the last of the ancient Egyptians died.

The Rosetta Stone

The answer lay within a slab of black granite. In 1799 in the Nile Delta, in a town called Rosetta, one of Napolean’s soldiers found a special stone as they demolished an old wall to extend their fort. Later named the Rosetta Stone, the artefact they found had three different languages engraved on the side; hieroglyphics, demotic, and Greek. Scholars were unable to understand the first two languages, but they could read Greek writing. They discovered the writing was about king Ptolemy V, who once ruled Egypt in 196 BC, and realised that the three languages must tell the same story. This marked the moment It became a very small ‘dictionary’ to the researchers attempting to understand hieroglyphics, and though this was vital progress, there were many challenging years ahead before anyone truly understood hieroglyphs.

Cartouche of Sekhemre-Heruhirmaat Intef or Intef VIII. 17th Dynasty. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London.

Thomas Young

A young English polymath was enthralled by the Rosetta Stone and made a breakthrough after focussing on a set of circled hieroglyphs called a cartouche. He believed that because these sets were made to stand out so much that they must be significant, perhaps the name of the Pharaoh Ptolemy which he knew was mentioned in the Greek translation. Young was able to decode the phonetics of the corresponding hieroglyphs because a pharoahs name would be pronounced very similar regardless of which language you were speaking. He spent time matching the letters of ‘Ptolemy’ allowing for the first correct understanding and verbalisation of hieroglyphs in almost a millennium and a half. But research went again the commonly held belief that hieroglyphs were ‘picture writing’ and not a phonetic language that could be spoken, and rather just symbols for items and people. Though he was really onto something, Young lost interest in his work, potentially with reluctance to challenge this widely accepted view. He explained his findings as foreign names being spelt out as there would have been no symbol for them, but it wasn’t long before this theory was challenged and proved wrong.

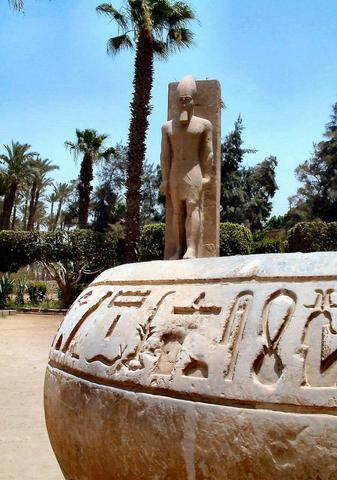

Hieroglyphs in Memphis with a statue of Ramses II in the background.

Jean-François Champollion

Champollion picked up where Young left off and promised he would be the one to crack the ancient code after seeing a collection of Egyptian antiquities in 1801 when he was just ten years old. In 1822 he received some cartouches that contained traditional Egyptian names but found they were still spelt out which directly disapproved the theory that spelling was only for foreign names. He used Young’s method on a few more cartouches, and eventually found himself focussed on one cartouche that contained just four hieroglyphs. He didn’t know the first two symbols but it had already been established that the two repeated at the end must be ‘s-s’. Champollion had learnt to be fluent in Coptic as a teenager, and would write his journal in the archaic language, but had never thought that Coptic might be the language of the ancient hieroglyphs. He considered the first hieroglyph, and assuming its sound to be that of the Coptic word for sun, ‘ra’. This would make the cracked code ‘ra-?-s-s’, and only one pharaonic name fit this – Rameses. And with that, Champollion had cracked hieroglyphs and solved the centuries-old mystery. Egyptian hieroglyphs were the formal writing system used in Ancient Egypt to write the Coptic language, and Champollion had opened the doors to understanding these ancient communities and culture.

For more science and technology articles, pick up the latest copy of How It Works from all good retailers or from our website now. If you have a tablet or smartphone, you can also download the digital version onto your iOS or Android device. To make sure you never miss an issue of How It Works magazine, subscribe today!

Other stories you may like:

Who was the longest serving Pharaoh of Egypt?

The Egyptian mummification process

Buried in a bundle