Dr John Oxford on the Spanish Flu; “We’re still getting pandemics and we better get ourselves prepared”

The Spanish Flu of 1918 claimed the lives of between 3 – 5 percent of the world’s population. While war waged on the Western front, this microscopic assassin spread around the globe, carried by the soldiers drafted from across the globe. We spoke to Dr John Oxford, a leading virologist from Queen Mary, University of London.

The Spanish Flu was unusually deadly, and it spread so fast across the world. What was the impact of this pandemic?

In the period of 18 months it was global, maybe as many as 50 million people died, maybe 100 million. That puts the Spanish Flu into a category of its own – you might think of bubonic plague, and everyone does think of bubonic plague when they think of great infections, but this excelled bubonic plague. Bubonic plague is recognised as an important infection but nowhere like the impact of the Spanish flu.

Members of the American Red Cross remove a victim of the virus from a house at Etzel and Page Avenues, St. Louis, Missouri

Could it happen again?

The Spanish flu is the biggest outbreak of any infection either then or now. We have to take it very seriously all these years later and were obliged to look at it and say why did that virus do what it did, how did it do it, did it have some special virulence factor and could we possibly have a return of it. By understanding the Spanish flu, we can somehow protect ourselves against influenza that could do the same again. I don’t think we can forget and relax, we must still take it seriously, and we must plan for these recurring pandemics and unless we plan we could be caught nastily. We’re still getting pandemics, and we’ll continue to get them.

Today the onset of the flu is usually just associated with some aches and pains. Were the symptoms in 1918 very different?

Actually, the symptoms were much like the symptoms today. You have a rapid onset; headaches, aches and pains, a desperate desire to go to bed. You just couldn’t continue, you had to go to bed, which is a key feature of the infection then and now. But with this outbreak, they would go blue. They would have this Heliotrope cyanosis. It’s a very unusual colour – their face would take on this lavender hue, their lips would go blue, their ears would go blue.

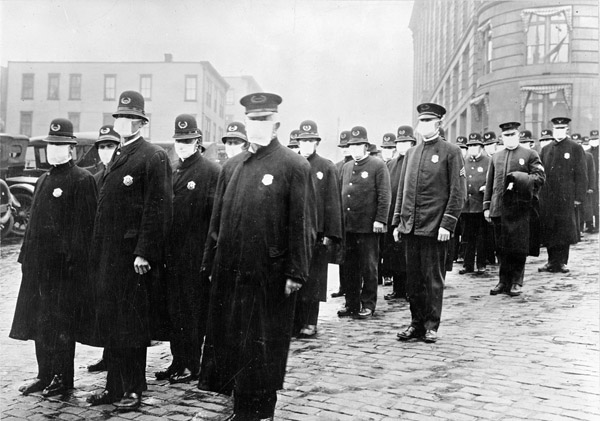

In many parts of the world, masks were made mandatory in public to prevent the spread of the disease

And was that when the nurses would know they were very sick?

Yes, they would die. Nearly all of those with the cyanosis would die, and a nurse or a sister could come into a ward and look down the beds, look for the cyanosis, and say ‘look, those three, we can have three more people on this ward tomorrow”. It was soon noted that blood was around when dealing with this virus – that you suddenly wake up with blood all over the sheets. People were bleeding from their noses quite strong nosebleeds or bleeding from their mouths, and there was one or two that bled from their ears. A lot of sputum, and a lot of blood. So it began to develop a nasty, well deserved, reputation.

We have seen a few cases of bird flu over the last few decades, and there seemed to be a lot of hysteria surrounding them. What causes these outbreaks and is it a cause for concern?

These pandemic influenza viruses are basically bird viruses, that is their natural host, the natural host – migrating birds, ducks, swans, geese. They infect them in the gut – the birds aren’t ill – and they start the migration route. They are inadvertently infected with all kinds of influenza virus, and they will come in contact with local chickens particularly. The virus then moves from the migratory to the local ones. The local ones are under more stress; they’re usually battery fed, squashed together in farms, they begin to get ill, the migratory move on. And then the keepers are at risk themselves of picking up the influenza virus, and then that virus can move from the keeper to the family and to move out to their friends. That’s the route we think, and we think that happened in 1918, and [the later outbreaks of] 1957, 1968, and 1976 and 2009. You can’t stop migrating birds, so you have a problem. We’ve had them in the past, we will continue to have them, and we better get ourselves prepared.

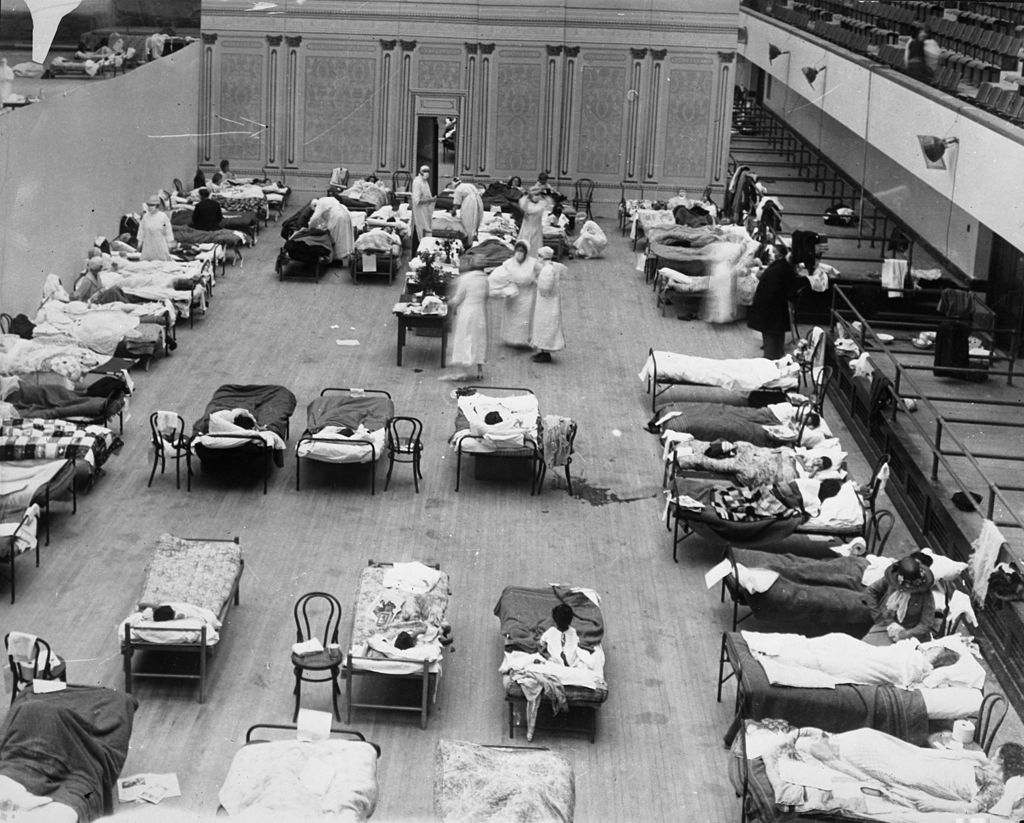

The Oakland Municipal Auditorium during 1918 when it was used as a temporary hospital

There are regular outbreaks of different viruses, but they always seem to stay quite contained. Even the Ebola crisis was contained within a few months. What made the Spanish Flu outbreak unlike any other we have seen?

It was the British Empire – we were the dominating country in the world. All of our armies had been pooled in from every nation of the world part of the British Empire, and they wanted to go home. The ships of the navy took them home, and they began classic outbreaks. India, Australia, New Zealand, wherever you think the British Empire, we know it had returning soldiers, and they returned with this virus.

And it was that mass movement that contributed to the outbreak?

The pandemic was all tangled up in the war – without the war I don’t think we would have had the pandemic. Whoever was responsible for that goings-on, they also have to take responsibility for the 50 million people who died in the pandemic. We can conclude from that if you’re a politician and you start indulging yourself in war mongering you have to be pretty careful and take responsibility for these pandemics.

For more information about science and technology, visit our website now. If you have a tablet or smartphone, you can also download the latest digital version onto your iOS or Android device. To make sure you never miss an issue of How It Works magazine, subscribe today!

Other articles you might like:

How do viruses and bacteria differ?

HIV virus is becoming weaker and could lead to the end of AIDS

New antibiotic discovered in soil could fight resistant diseases